We all know that market determined prices reconcile supply and demand. Higher prices discourage demand and encourage supply. What is true of an individual price is true of all prices on average, as represented by a Consumer Price Index(CPI) That prices generally tend to rise with increased demands or reduced supplies and vice versa seems obvious enough.

Higher prices discourage demand and encourage supply. That prices generally tend to rise with increased demands or reduced supplies and vice versa seems obvious enough. But the supply and demand for all goods and services are not determined independently of each other. The supply of all goods and services produced in an economy over a year is equivalent to all the incomes earned producing the goods and services that year. The value added by all producers (GDP) is equal to all the incomes earned supplying the inputs that produce output. Incomes are received as wages, rents, interest, dividends, taxes on production and what is left over, the profits or losses for the owners after all input costs have been incurred.

Produce more, earn more and you are very likely to spend more. The economic problem, not enough of everything, too little income, is surely not the result of any reluctance to spend on the necessities or luxuries of life. The problem is we do not produce enough, earn enough income to spend really more.

Extra demands can be funded with debt. Yet for every borrower spending more than their incomes, there must be a lender saving as much. Matching financial deficits with financial surpluses, is the essential task of financial markets and financial institutions, and may not happen automatically or seamlessly. There may be times when the demand for credit and the spending associated with it may run faster or slower than the supply of savings. If so incomes and output may increase temporarily above or below long-term trends. We call that the business cycle. Interest rates (yet another price) may be temporarily too low or too high to perfectly much the supply of and demand for savings. But such imbalances must sooner or later will run up against the supply side realities, the lack of income.

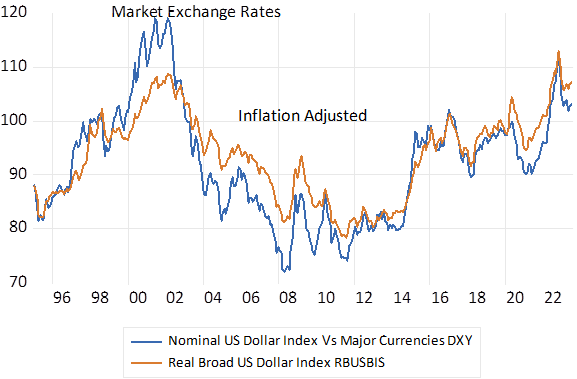

There is a further complication. The supply of goods and service is augmented by imports. And demand includes demand for exports. In South Africa both imports and exports are each equivalent to about 30% of the economy, making a large difference to supply and demand. But the prices of these imports and exports are not set in South Africa. They are set in US dollars and translated into rands at highly unpredictable and generally weaker exchange rates. The prices paid for imports and exports affect average prices. And they mostly push the averages higher. It has been the case in SA of a weaker exchange rate leading, equivalent to a supply side shock, and prices following.

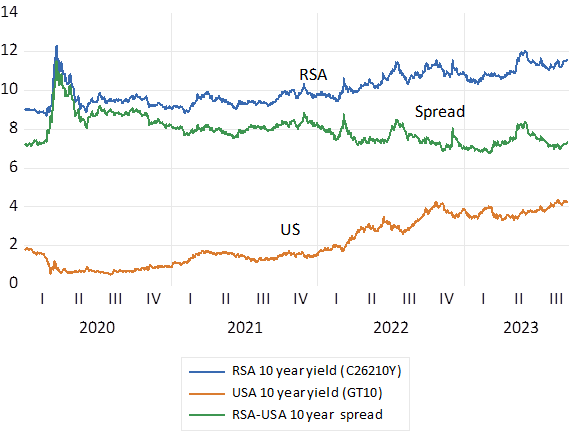

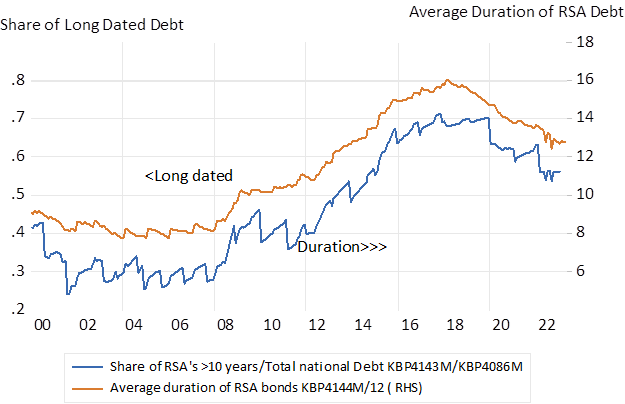

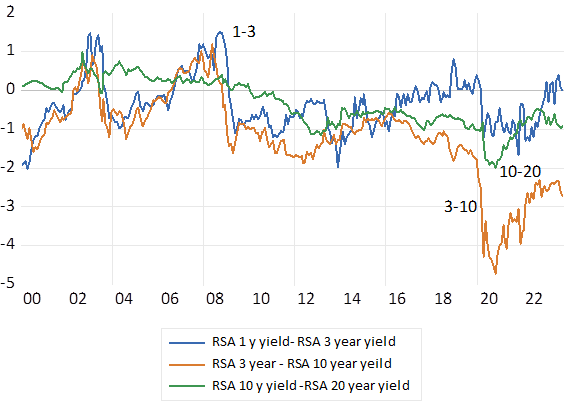

And the rand is still expected to depreciate against the dollar by more than the difference between SA and US inflation. The bond market expects the rand to weaken against the USD by an average 7.3% p.a. over the next ten years, being the spread between RSA bond yields (12%) and the US yield(4.7%) While the difference in inflation expected in SA (7.2% p.a.) and in the US (3.2% p.a) over the next ten years is much less, only 4.8% p.a. according to the break-even gap between vanilla bond and inflation protected bond yields.

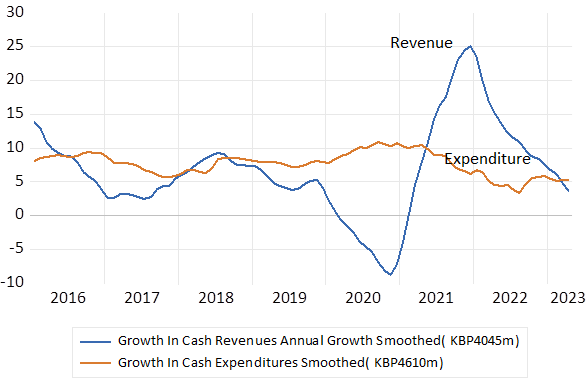

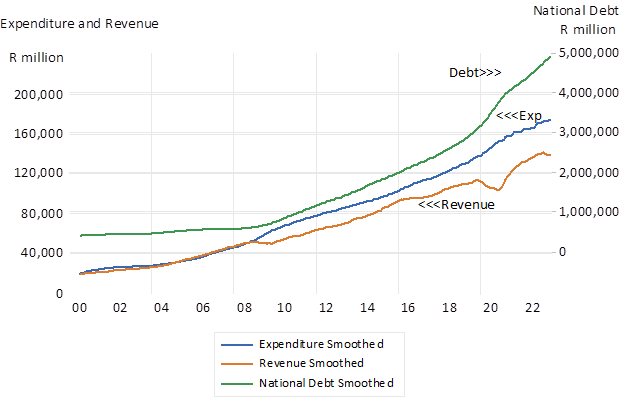

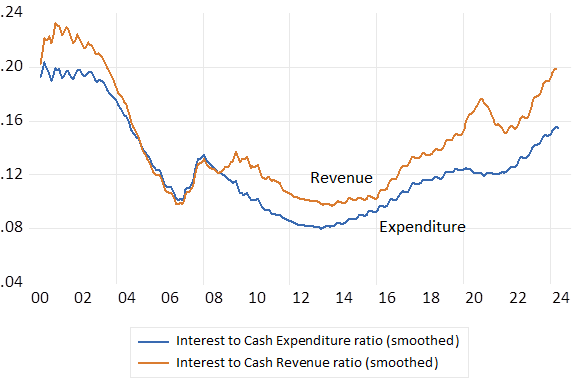

Lenders to the SA government remain suspicious of SA’s ability to grow fast enough to raise the taxes that could sustain fiscally responsible policies. That is the government will not avoid resorting to funding expenditure with money supplied by the central and private banks. A sure source of extra demands without extra supply that leads to ever higher prices as it does persistently in most African countries.

There is little monetary policy and short-term interest rates can do to strengthen the rand and bring inflation down further against this backdrop. That is without resulting in too little demanded and even less supplied than would be feasible. That in turn bringing still slower growth more fiscal strain, higher borrowing costs and a still weaker rand- and higher prices. The call is not to inhibit already depressed demand but for economic policy reforms that would stimulate the growth in SA output and incomes enough to change the outlook for fiscal policy, the exchange rate and inflation.