There is a certain balance of payments (BOP) outcome. That the dollar payments and dollar receipts in the currency market will strictly balance over any period- an hour, day quarter or year. The exchange rate and interest rates will continuously adjust to make it so- to equalize supply and demand for dollars and other currencies traded. And it is a very good idea for the authorities not to intervene in or attempt to influence this market determined exchange rate with interest rate adjustments. Or to directly control demands for or supplies of foreign currencies to achieve a temporarily better, perhaps less inflationary rate of exchange. A shadow market will emerge to siphon off undervalued dollars, leading to an official scarcity of dollars. Making it very difficult to do normal helpful income enhancing business across the frontiers and discouraging to foreign investment so important to any economy. As MTN knows only to well from its experience in Nigeria.

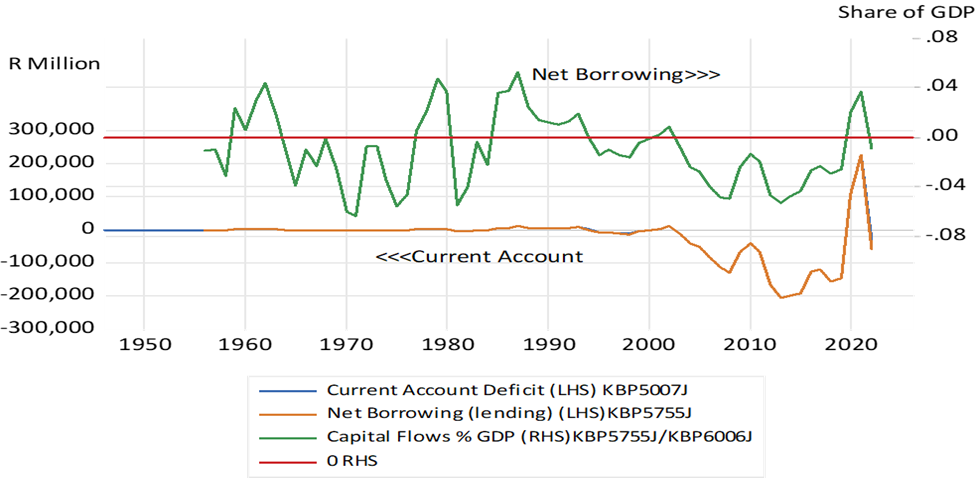

Another BOP relationship will also always hold. The current account of the BOP- that measures payments and receipts for imports, exports and the flows of dividends and interest paid or received by South Africans, will always be matched equally and oppositely by what are measured as flows of capital over the exchanges. A current account deficit will always be matched by a capital account surplus of the same amount and vice versa. There is no cause-and-effect relationship implied by this identity. The current account does not determine the capital flows – any more than the capital flows determine net flows of foreign trade, interest, and dividend payments. It is an accounting identity.

The capital and current accounts- an identity, identified.

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

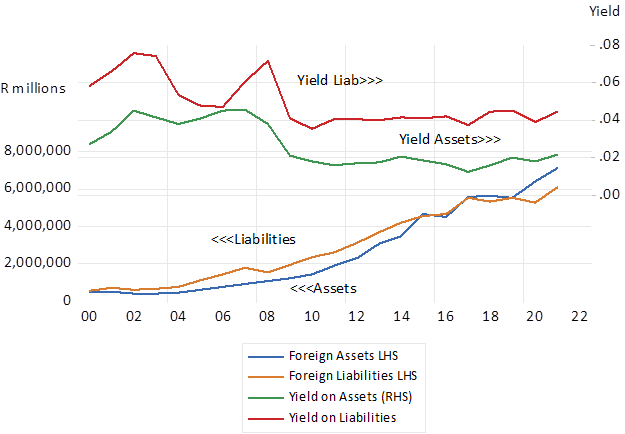

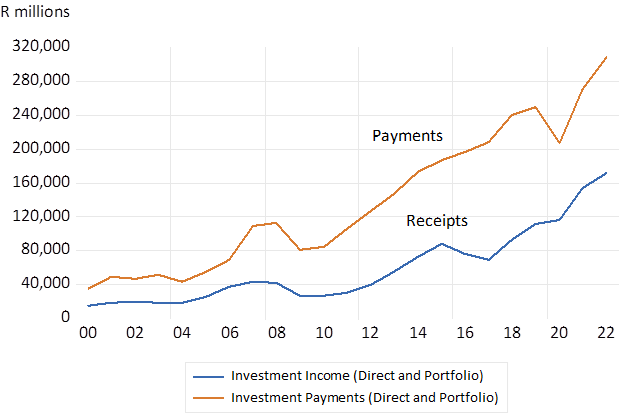

Over most years the current account of the SA balance of payments has been in deficit. Exports of goods and services almost always exceed imports – generating a consistently positive balance of trade (BOT) While the deficit on what might be described as the asset service account, dividends and interest payments, almost always exceeds dividend and interest received by enough to exceed the positive BOT. The interest and dividend yields on SA liabilities much exceeds the dividend and interest yield on SA assets held abroad. But between 2020 and 2022 South Africa ran current account surpluses and exported capital on a significant scale. So much so that the market value of SA assets held offshore now exceeds that of the market value of foreign owned assets in SA. This was not good for the South African economy.

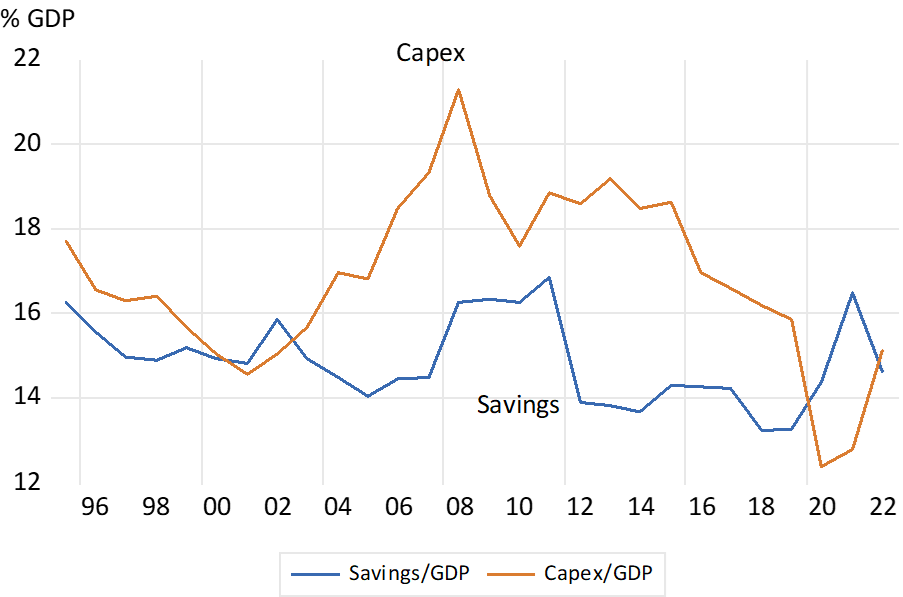

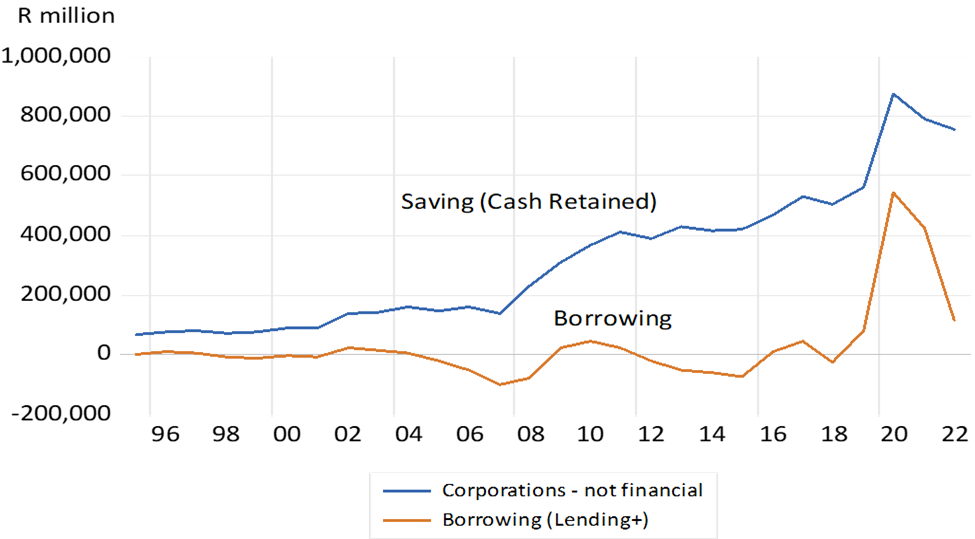

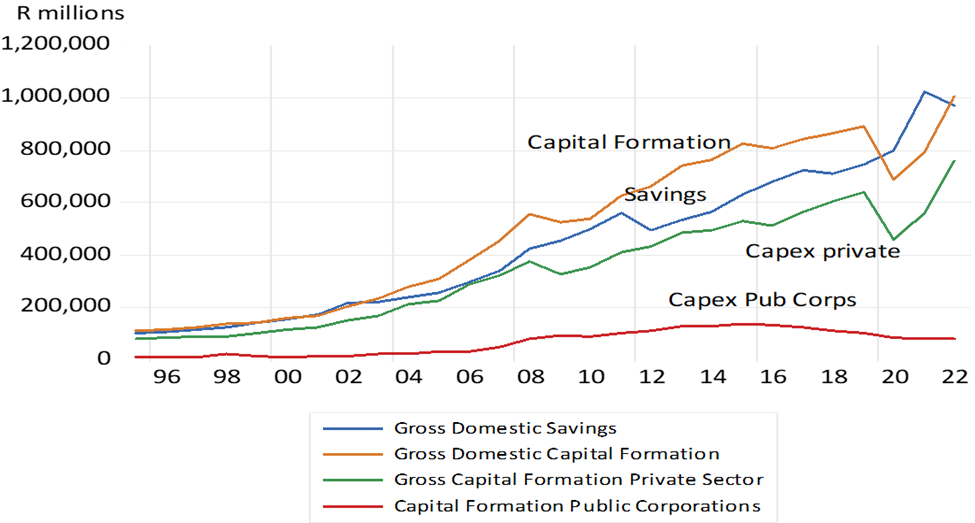

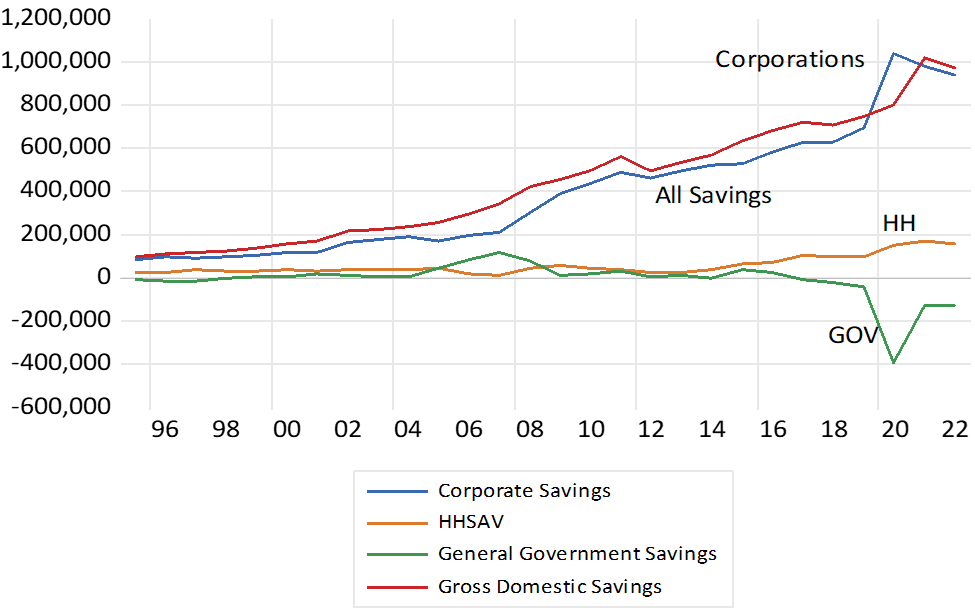

There is a National Income Accounting Identity to help make the point. The current account deficit also equates to the difference between Aggregate Incomes that are equal to Aggregate Output (GDP) and Total Expenditure on final goods and services (GDE) It is also by definition the difference between Gross Savings and Gross Capex. Post Covid, Gross Savings, almost all in the form of cash retained by the corporate sector, held up better than Capex and capital – from a capital starved economy – flowed out.

South Africa, Gross Savings and Capital Formation – Ratio to GDP – Annual Data, Current Prices

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

South African Non-Financial Corporations; Cash from Operations Retained and Net Lending (+) or Borrowing (-) Annual Data

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

South Africa; Gross Savings and the Composition of Capital Expenditure by Private and Publicly Owned Corporations

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

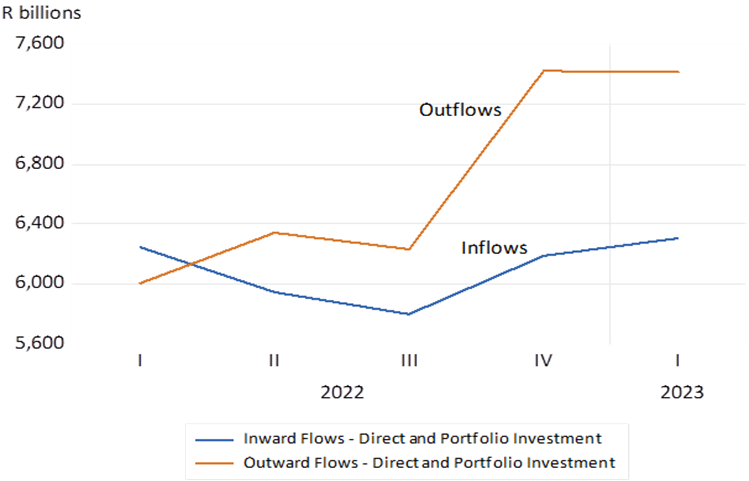

South Africa; Inflows and Outflows of Capital; Direct and Portfolio Investment. Quarterly 2022-2023

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

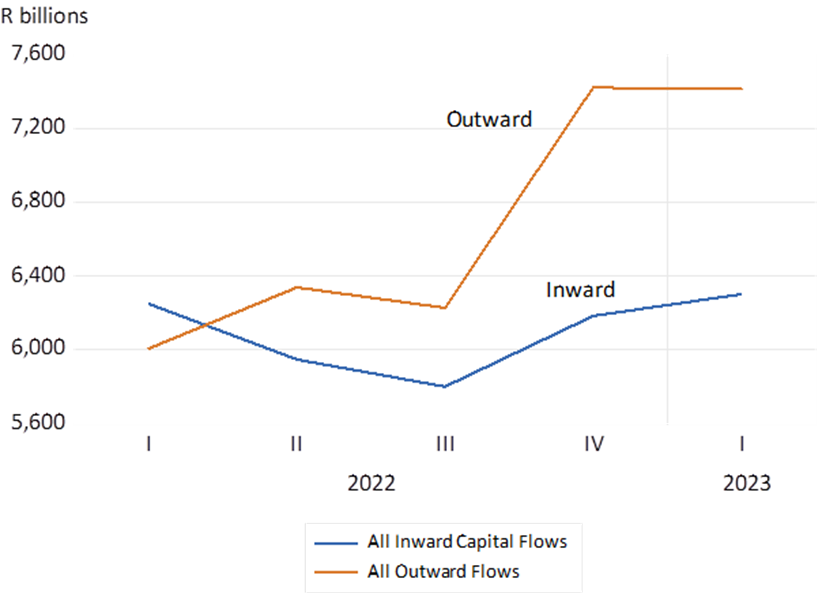

All Capital Flows to and from South Africa; Quarterly Data (2022.1 2023.1)

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

SA; Total Foreign Assets and Liabilities; Direct and Portfolio Investments and Yield

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

SA Foreign Investment Income (Dividends + Interest) Annual Data

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

South Africa; Gross Savings Annual Data (R millions)

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

Both the ratio of Gross Savings – and Capex to GDP can be regarded as unsatisfactorily low in SA. The opportunity to raise the savings rate seems limited, given low average incomes. However, the opportunity to raise the rate of capex to GDP and to attract foreign capital to fund income growth encouraging capex and the accompanying larger current account deficits is always open. SA must be able to offer faster growth and the accompanying higher expected returns, to attract more foreign capital and to retain a greater share of domestic savings.

Supply side reforms are urgently needed for the SA economy. We all know what they are. Demand will keep up with supply automatically. Extra Supply – extra incomes earned producing more goods and services- creates its own demands. Yet until the economy can deliver more growth and better returns, the best we can do with our savings is to invest them abroad. (including buying shares of companies listed on the JSE that do almost all of their business outside the SA economy) Without such opportunities, the pension and retirement funds, upon which we depend for our future income, would be in a truly parlous state.