South Africa needs a plan to reduce the national debt and interest bill

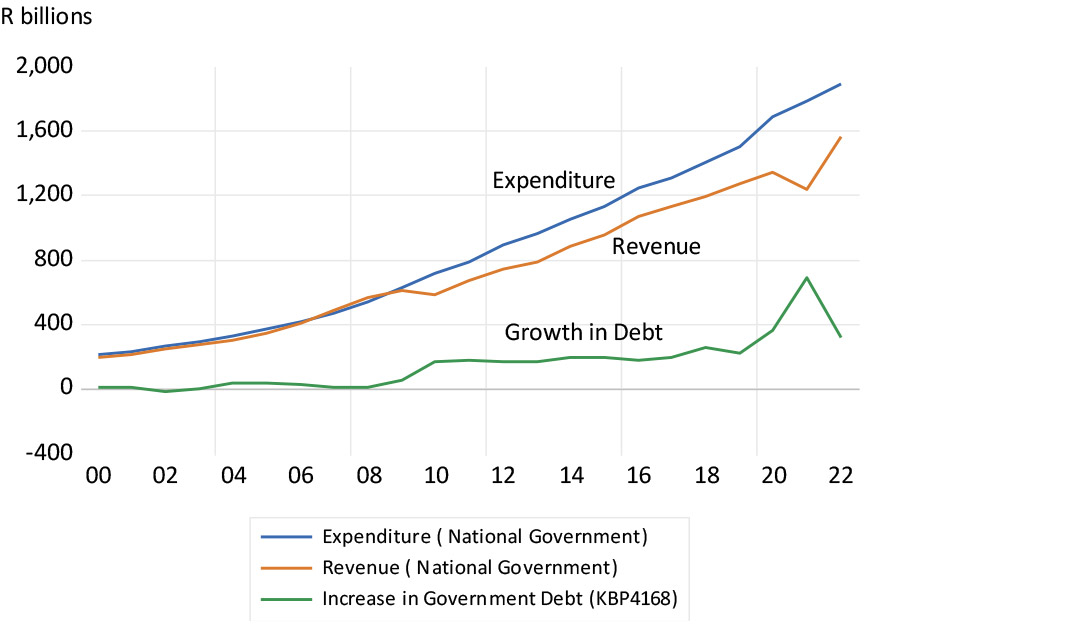

The national debt and the interest bill for SA taxpayers have grown sharply since 2010 – the national debt grew by over R200bn before the Covid-19 lockdowns and by over R400bn in 2021. This year, taxpayers’ interest bill will be of the order of R300bn, compared with R57bn in 2008, while the national debt will approach R4 trillion, equivalent to about 60% of GDP – from a mere 18% in 2008. This is a dangerous trend that needs to be reversed.

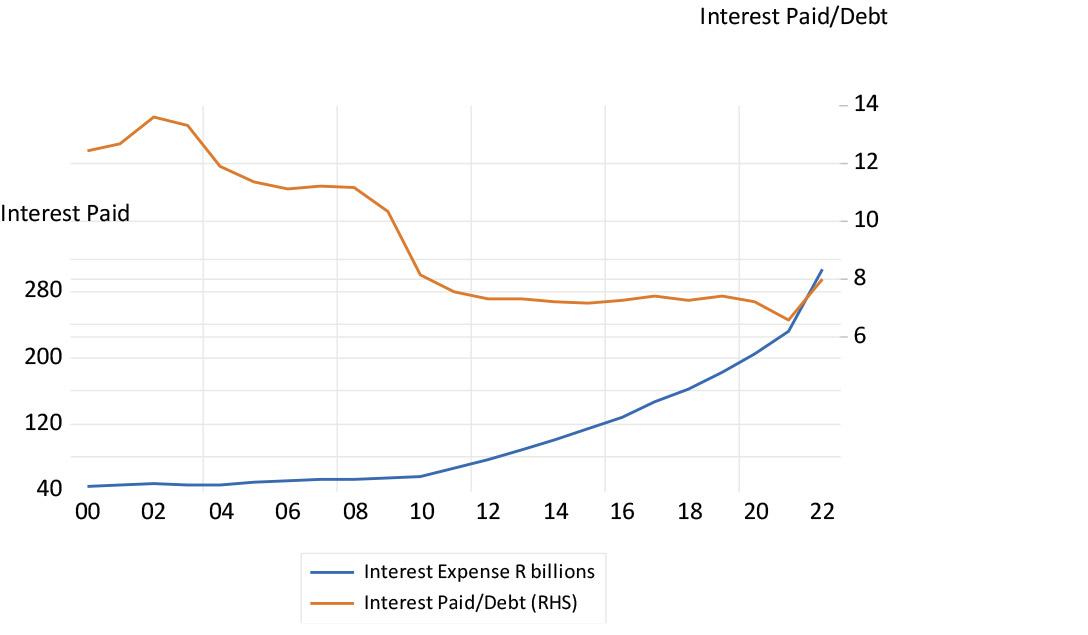

In 2008, the interest bill accounted for 8% of all government spending but has since doubled to 16%. At an average 8% yield on the debt, every 1% increase in the average cost of funding the debt adds about R32bn to the interest bill. As the real national debt increases, taxpayers and voters may become unwilling to keep paying this overwhelming interest bill. Destruction of wealth through inflation of the value of the outstanding local currency-denominated debt will then follow. These types of developments do not come as a surprise to investors. History has made them aware of the dangers of default and they demand compensation for the risks of funding national debts, in the form of higher interest rates paid for upfront.

SA government growth in expenditure, revenue and national debt

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 10/11/2022

In this context, South Africa has been penalised for its presumed inability to reverse course on its fiscal trajectory. High interest rates paid by the government and then passed on to businesses have compensated lenders for expected inflation and the expected accompanying weakness of its currency. The expected weaker rand detracts significantly from the expected returns of foreign investors earning rand incomes when converted to US dollars at some future point in time.

Government interest paid (R billions – LHS) and the ratio of interest paid to total debt (RHS)

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 10/11/2022

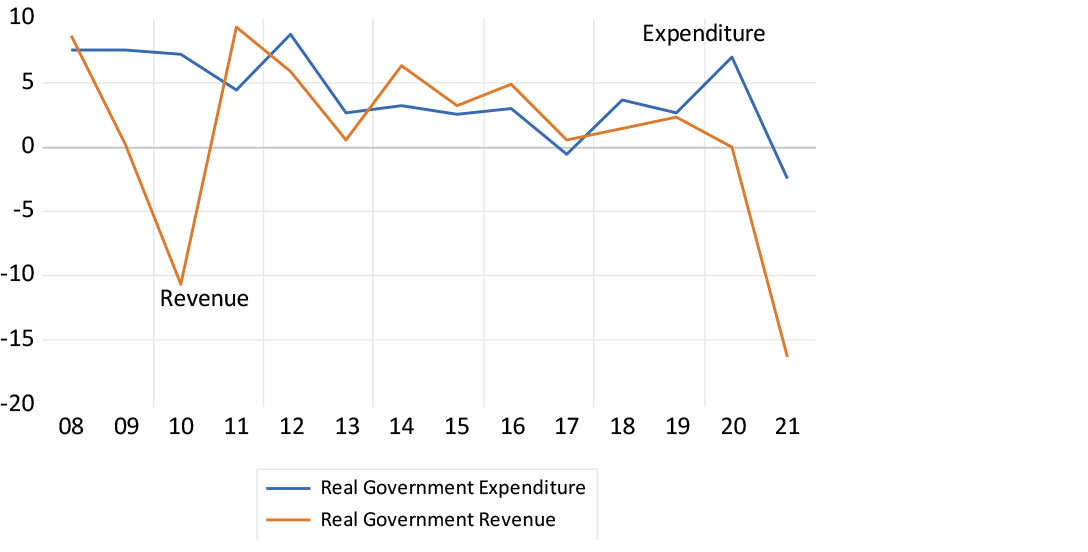

Looking closer at the cause of the rise in the national debt and interest bill, the chief culprit was government spending, which was sustained at a generous rate relative to real GDP after the recession of 2009 and 2010, while the revenue growth lagged. This problem was exacerbated by the lockdowns of 2021. Between 2008 and 2021, government spending after inflation grew by an average of 4% a year, while growth in real revenues increased by an average of 1.2% a year. Real revenues declined by 10% in 2010 and by 16% in 2021. The recession was bad news for the Treasury and higher tax rates were bad news for the economy.

Real growth in national government expenditure and revenue

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 10/11/2022

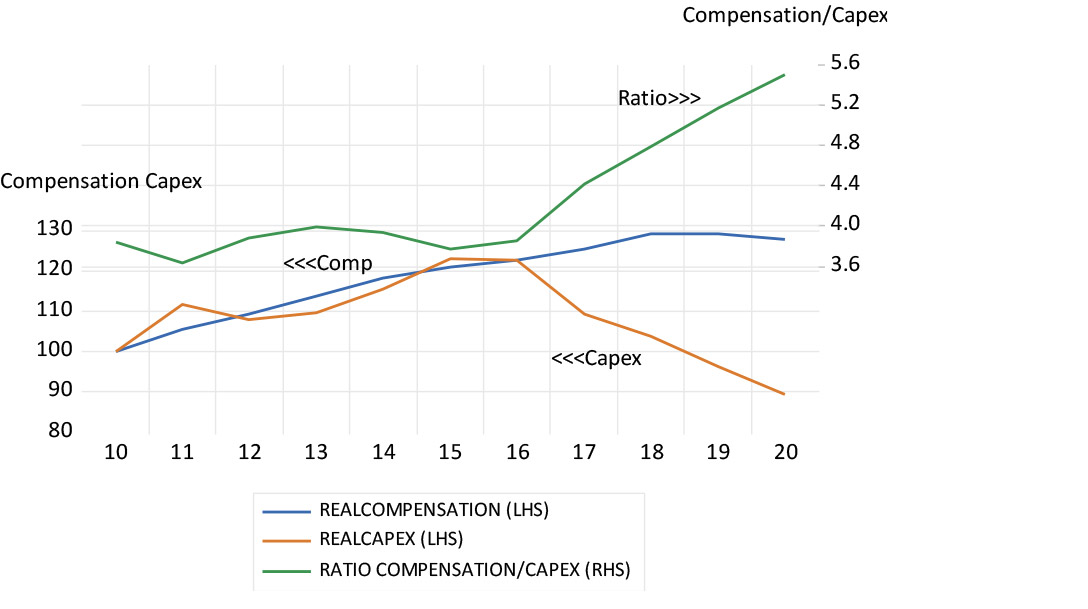

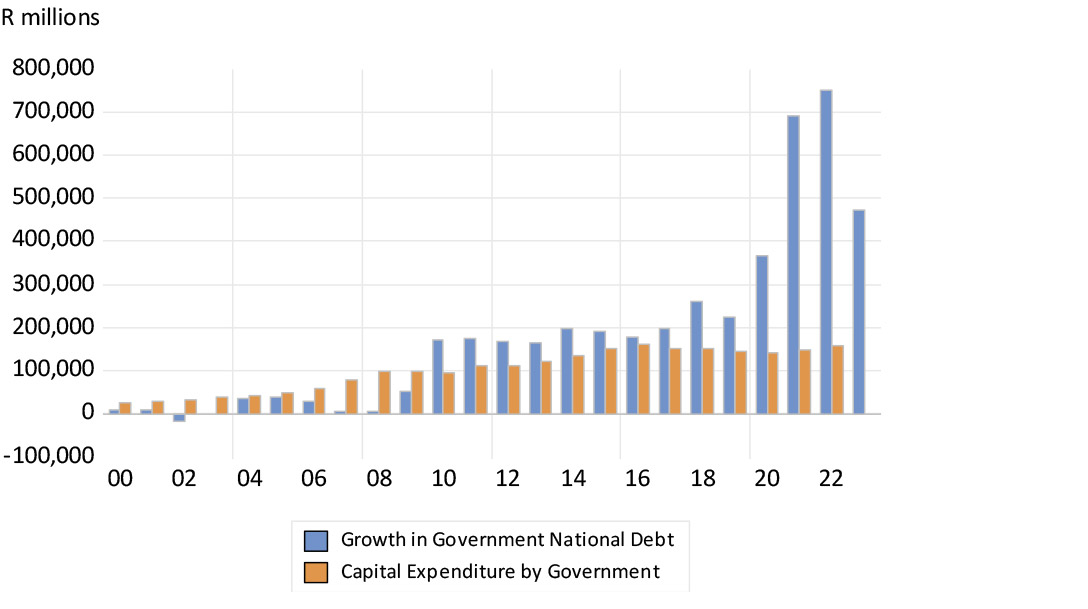

Much of the extra borrowing undertaken by the government since 2008 has been used to fund consumption spending rather than capital expenditure, a situation that is not helpful for growth. Real spending on compensation for government employees grew by about 30% between 2010 and 2018. Real capex by the government fell away sharply after 2015 and is now 25% below 2015 levels. The numbers employed in government have not increased meaningfully – it is average real employment benefits that have. An expensive patronage system seems to be at work.

Real general government spending on employee compensation and capital expenditure (2010=100, LHS) and the ratio of compensation to capex (RHS)

Source: SA Reserve Bank (Production and income accounts) and Investec Wealth & Investment, 10/11/2022

The call for fiscal sustainability made by Minister of Finance Enoch Godongwana in his recent mid-term Budget update is founded on the principle of restraining government spending on employee benefits. This is a restraint that is essential for promoting the long-term interests of all South Africans in economic development, including those who now work for or hope to work for the government.

Fiscal reform will be needed to achieve this sustainability. For example, it could extend beyond the objective of reducing the gap between government expenditure and revenue. The government could publish a capital budget and commit to raising national debt only to fund capex. This would help to permanently close the gap between government borrowing and government capex that was allowed to open up after 2008. Honest procurement of well-selected cost-of-capital beating projects should not be regarded as an impossible task.

Growth in national debt and capital expenditure by government

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 10/11/2022