While inflation rises across the globe, South Africa’s monetary and fiscal authorities should take note of the weak state of demand locally.

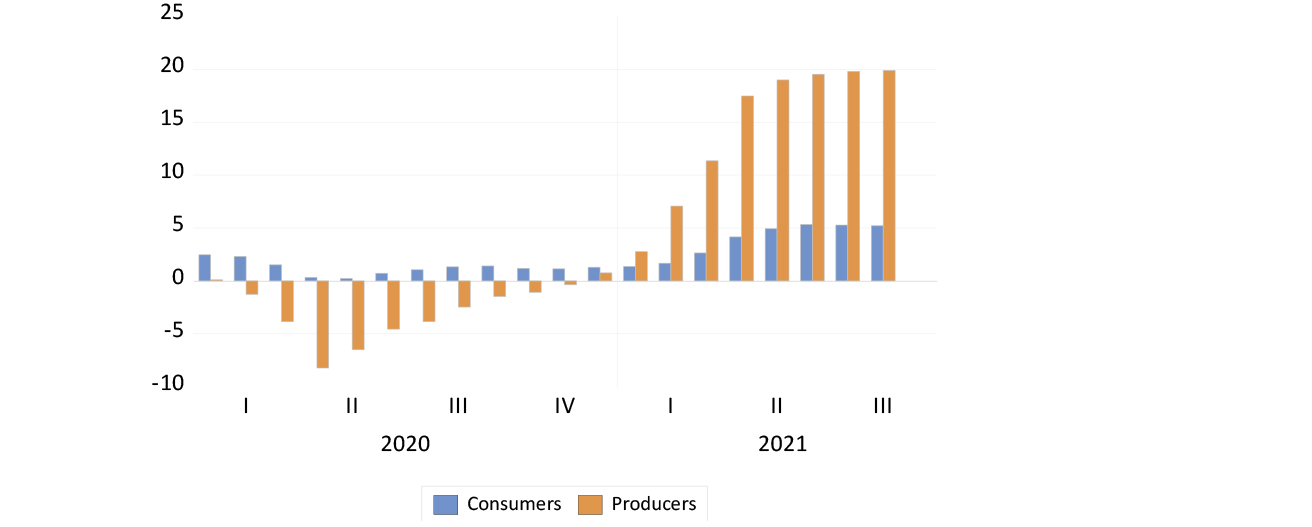

Prices are busting out all over the world. Prices charged by all US producers are 20% higher than they were a year before. Consumer prices were up by a ‘mere’ 5% in August, and that was before the recent tripling of natural gas prices.

US headline inflation rates (annual percentage growth in consumer and producer prices)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Investec Wealth & Investment, 6 October 2021

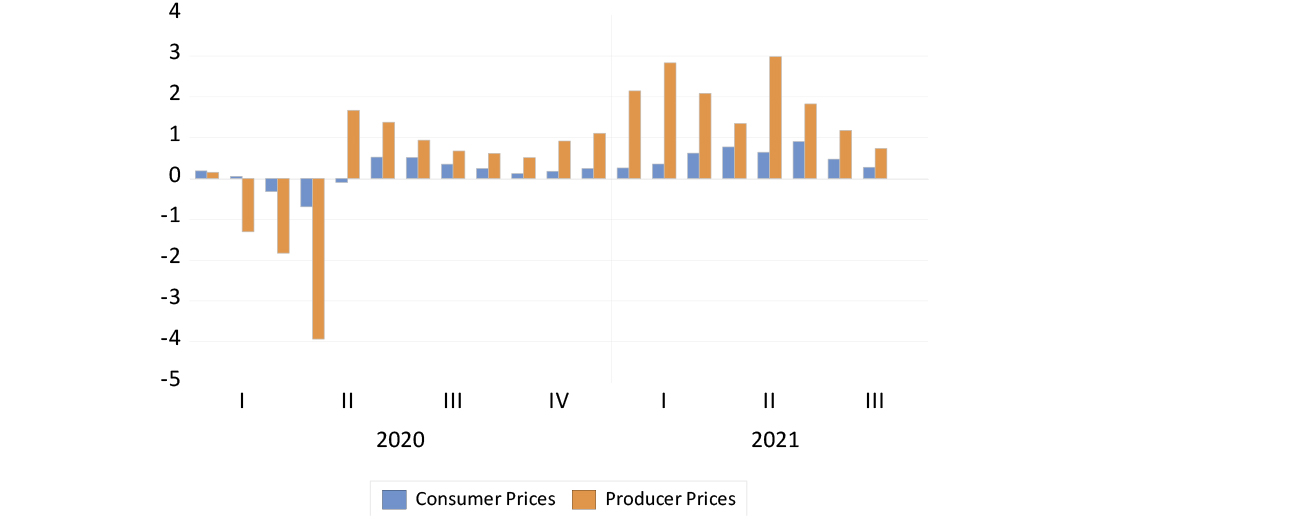

US headline inflation rates (monthly percentage growth in consumer and producer prices)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Investec Wealth & Investment, 6 October 2021

The cause of higher prices is clear enough. They are a response to buoyant demands stimulated by Covid-inspired extra government spending and central bank funding of much larger fiscal deficits that have dramatically increased the supply of money (bank deposits) held by households and firms. In the US, these savings have also reduced the incentive for people to get a job – of which there is an unusual abundance, as firms struggle to match surprising strength in demand with extra output and willing workers.

This mixture of strong demand with constrained supply has caused prices to rise. The effect of higher prices is also predictable. Higher prices reduce demand while they serve to encourage extra output. They also act as a drain on disposable incomes and spending power. Higher prices, particularly when they respond to supply side shocks, can therefore lead to slower growth as these higher charges work their way through the economy.

What is critical therefore for the control of longer-term inflation trends is how the monetary and fiscal authorities react to this slower growth. Should they attempt to mitigate the impact of higher prices on growth by stimulating demand for goods, services and labour, then the temporary surge in inflation can become longer lasting. Firms and trade unions will then budget for expected and uncertain inflation.

Central bankers believe that inflation depends on inflation expected, modified by the state of the economy. Independent central banks accept responsibility for the state of demand, but they hope that inflation expectations are anchored at low rates, to make their task of containing inflation an easier one. The markets, to date, have largely believed that the observed rise in inflation is a temporary one. But the markets will be watching the reactions of the fiscal and monetary authorities closely for signs of the policy errors that can turn a temporary supply side shock into enduringly higher inflation.

South Africa – not a typical case

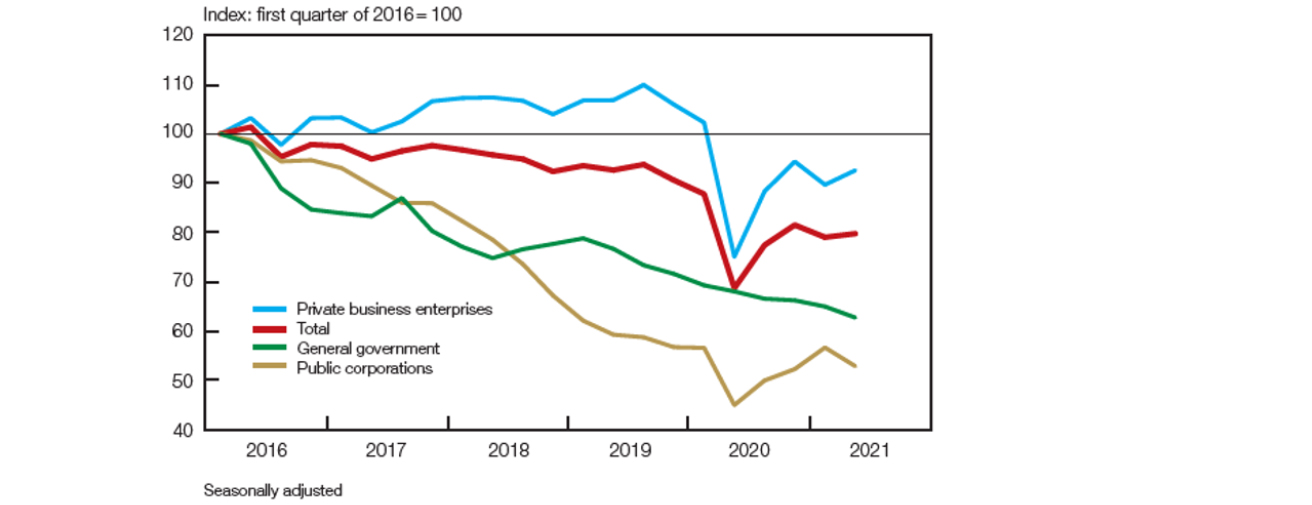

It is striking how the South African economic circumstances have not been typical. We too will have to deal with an energy price shock that will depress demand. But demand already remains depressed. Particularly depressed since 2016 have been the demands of firms, including the public corporations, for plant, equipment, workers and credit.

Real gross fixed capital formation by type of organisation

Source: Stats SA, SA Reserve Bank, 28 September 2021

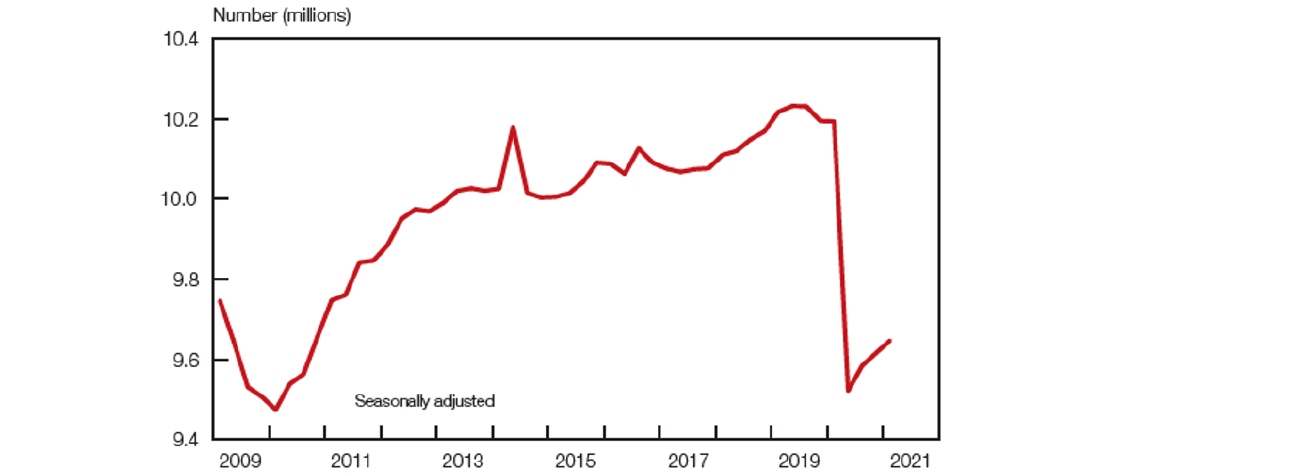

Households have helped to sustain spending, but only a little. Total spending by households grew by 1% in the first quarter of this year, but only by half as much in the second quarter. Those in jobs have earned more, yet many more (over a million) have lost their jobs since the lock downs. Formal employment outside agriculture is now below 2009 levels.

Formal non-agricultural employment

Source: Stats SA, SA Reserve Bank, 28 September 2021

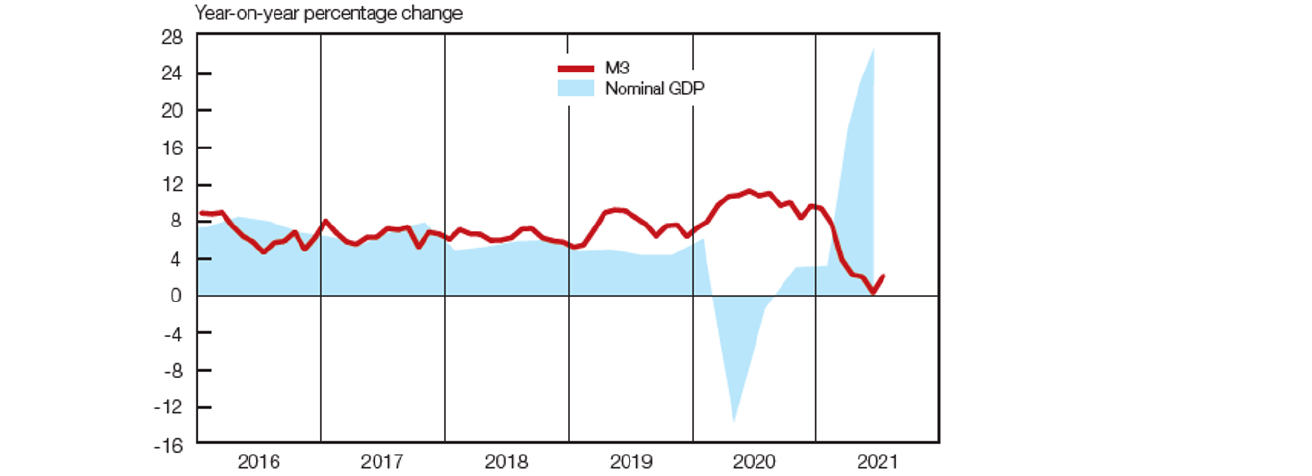

The money supply has flat lined as nominal GDP has grown strongly. The closely watched government debt-to-GDP ratio has been further reduced by extraordinary growth in government revenues. Tax receipts have accelerated in response to the global inflation of metal prices that make up the bulk of South Africa’s exports; so much so that the total borrowing requirement of the government in all its forms has declined from 13.5% of GDP in the first quarter of last year to as little as 1.8% of GDP in the second quarter of this year. Fiscal austerity has been practised in Covid-ravaged South Africa. And monetary policy, judged by its effects on money and credit supply, has not been accommodating enough.

Money supply and gross domestic product

Source: Stats SA, SA Reserve Bank, 28 September 2021

The output gap – the potential supply exceeding realised spending – is likely to remain persistently wide. Inflation expectations therefore remain unaltered. The case for higher interest rates to further depress demand seems weak in the circumstances. Yet the gap between short- and long-term interest rates has widened further in recent days. This implies an expected doubling of policy determined rates over the next three years.

The slope of the SA yield curve (SA 10-year yields minus money market rates)

Source: Bloomberg, Investec Wealth & Investment, 6 October 2021

The bond market indicates that any improvement in South Africa’s fiscal circumstances is sadly expected to be temporary rather than permanent. It can prove otherwise with fiscal discipline and sympathetic monetary policy.