The markets for industrial and precious metals are demonstrating some important truths. The price of iron ore, approximately USD 92 dollars per ton this week was more than twice as high, 200 dollars, in early July. Its price is as hard to predict today as it was a year ago when it sold for a mere USD85 ton. The pace of the recovery of the global economy after the lock downs was unusually unpredictable and proved surprisingly strong to increase the demand for steel and iron ore and other industrial metals. It is an expected slow down in global growth rates and so in the demand for steel and other industrial metals in the months to come that has caused prices to fall back as surprisingly.

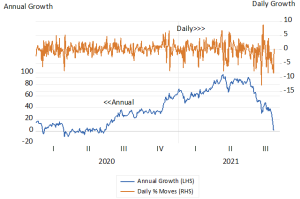

It should be recognised that there is no predictable cycle of the price of any well traded metal, currency, share or bond to assist timing an entry or exit to the market. Were there any regular cycle of prices or indeed of economic activity, that is a predictable trend towards peak growth rates, followed by a slower growth then a recovery from the trough – it would greatly help traders, producers or consumers to sell at the top and buy at the bottom. But such cycles are only revealed well after the events. They are the result of smoothing the data, comparing the outcomes to what occurred a year before, when almost all of the numbers overlap. Day to day, the data looks very different and the future of prices will not be at all obvious. They unfold as a random walk, with most prices having an almost 50% chance of rising or falling on any one day.

The annual and daily % movements iron ore spot price. USD per tonne.

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

Whether these random moves are drifting higher or lower to establish some persistent trend will only be discovered well after the event- perhaps only a year later. All we can attempt – and there is no lack of such attempts – is to model the forces of supply and demand that will determine prices or quantities in the future – as rationally as possible. And perhaps be bold enough to believe that your model will prove more accurate than the opinions revealed by current prices- that we know will vary with the news.

What happened in-between last year and now to the price of iron ore and similarly to the value of the platinum group of metals has had important consequences for the SA economy. They greatly boosted the SA balance of payments, tax revenues and the GDP. Dependence on capital inflows have become large contributions from South Africans to the global savings pool of over USD100billion p.a. as the foreign trade balance improved. Tax revenues have been growing well ahead of budget projections, approaching an extraordinary extra R250 billion of taxes, if maintained over a year.

And the GDP in current prices has risen almost as high as long term interest rates to help reduce the debt to GDP ratios. Yet long term interest rates remain at very high levels and are still particularly high relative to short rates, implying a doubling of short-term interest rates in three years- which would be very bad news for the economy. It is very difficult to make sense of this view of SA interest rates and monetary policy.

While annual growth rates may well have peaked, there is a lot more global demand still in the wings. Post-Covid stimulus continues to this day. The market judgment may be too pessimistic about demand and so prices and revenues may continue to be helpful for resource companies and the SA Treasury that shares in its profits.

How then should SA and resource companies react to such a further windfall? The answer should be obvious. That is look through any temporary surge or reduction in revenues and for the companies to pay out the unexpected extra cash to share or debt holders. For the Treasury it would be to spend no more and borrow less. The benefits to both parties in the form of lower long-term costs of raising capital would be large and permanent.