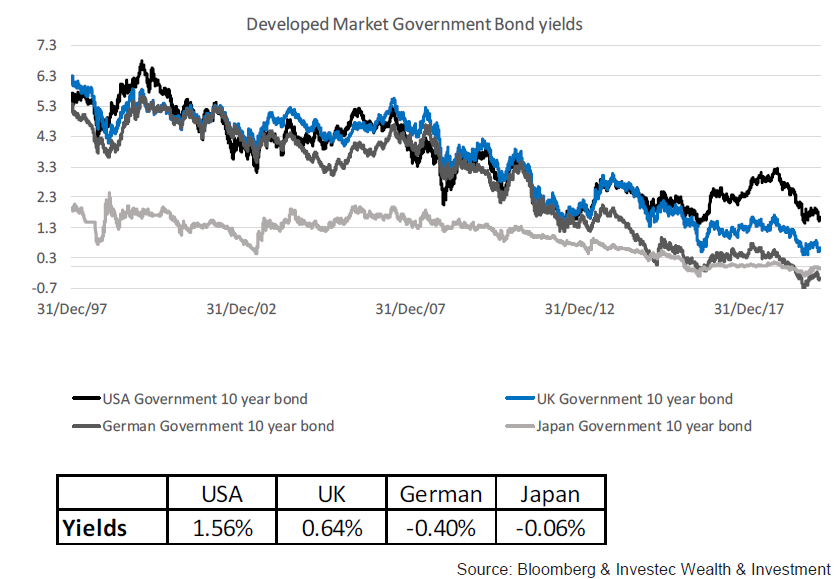

If we are to take seriously the signals from global bond markets- as we should- savers should expect a decade or more of very low returns. The decline in bond yields due to mature in 10 years or more accelerated dramatically during and after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) (see below)

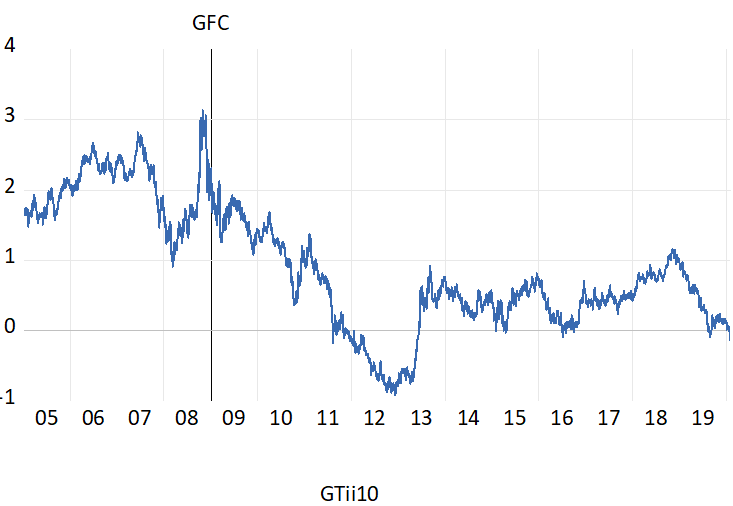

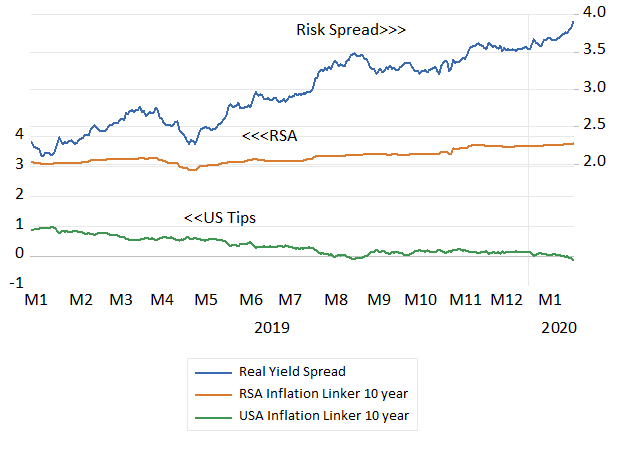

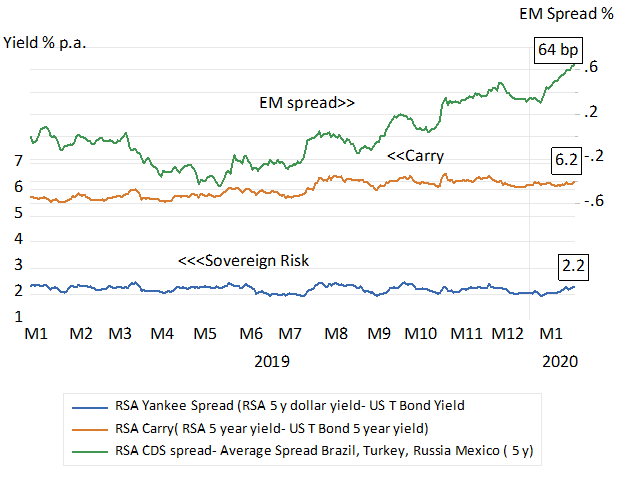

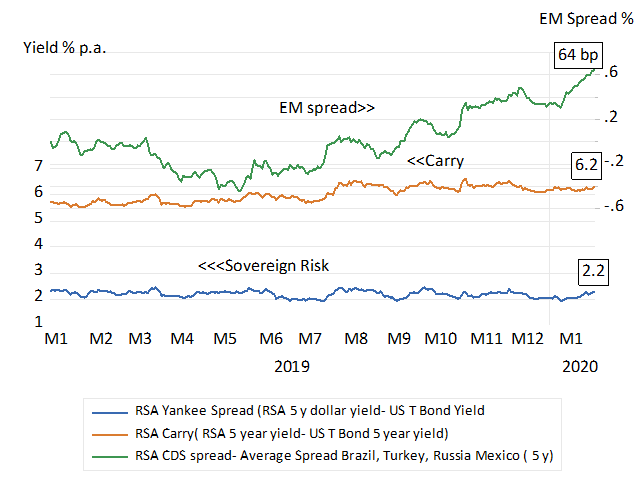

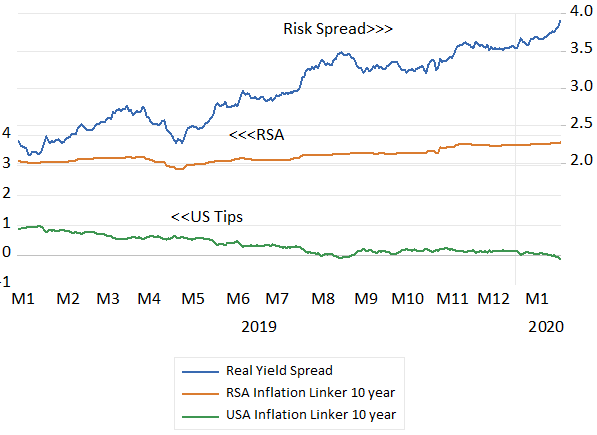

Less inflation expected is part of the explanation for these lower yields. But it is more than lower expected inflation at work. Yields on inflation protected securities – those that add realized inflation to a semi-annual payment – have declined to rates below zero. Before the GFC the US offered savers up to a risk free 3% p.a. return for 10 years, after inflation. The equivalent real yield today is a negative one of (-0.11% p.a). (see below)

Real Yields in the US 10 year Inflation Linked Bonds ( TIPS)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

These low risk-free rates also mean that firms investing the capital of their shareholders have very low investment hurdles to clear to justify their investment decisions. A 6% internal rate of return would be enough to satisfy the average shareholder given the competition from fixed interest. Equity returns might also be expected to gravitate to these lower levels.

Another way to describe these capital market realities is that the rate at which the value of pension and retirement plans can be expected to compound is expected to be at a much slower one than they have been in the recent past. Savers will need to save significantly more of their incomes to realise the same post-retirement benefits.

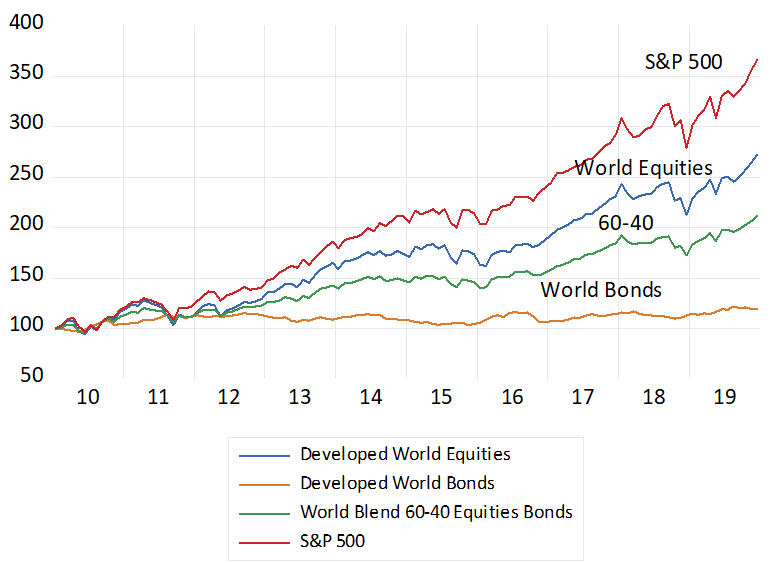

The past decade has in fact been particularly good for global pension funds. In the ten years after 2010 the global equity index returned 10.5% p.a. on average while a 60-40 blend of global equities and global bonds returned an average 6.4% p.a. with less risk. US equities would have served investors even better, realizing average returns of 13.4% p.a, well ahead of US inflation of 1.8% p.a. over the period.

Total portfolio returns 2010-2019 (January 2010 =100)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

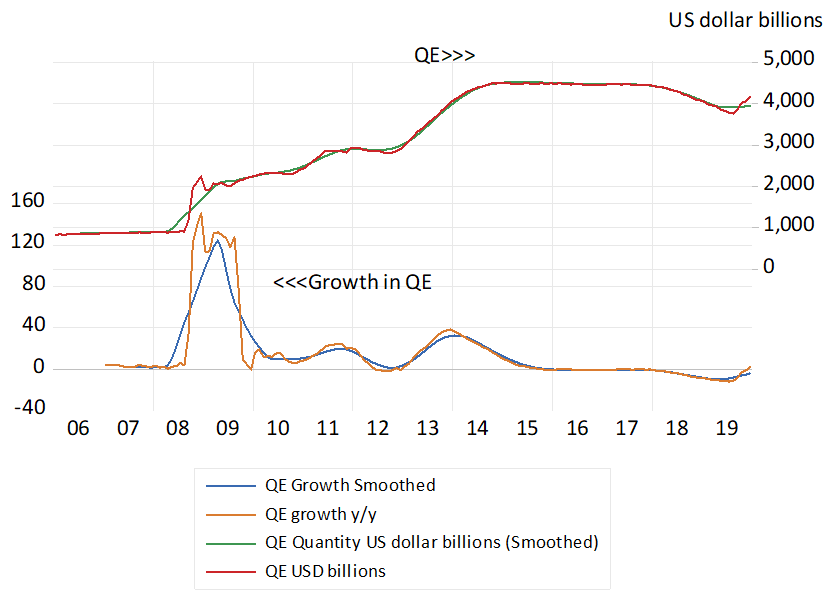

Why then has global capital become so abundant and cheap over recent years? Many would think that Quantitative Easing (QE) the creation of money on a vast scale by the global central bankers, has driven up asset prices and depressed expected returns. An additional three and more trillion US dollars-worth has been added to the stock of cash since the GFC.

Global Money Creation

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

But almost all of this cash has been added to the cash reserves of banks- and not exchanged for financial securities or used to supply credit to businesses that could have stimulated extra spending. Bank credit growth has remained muted in the US and even more muted in Europe and Japan.

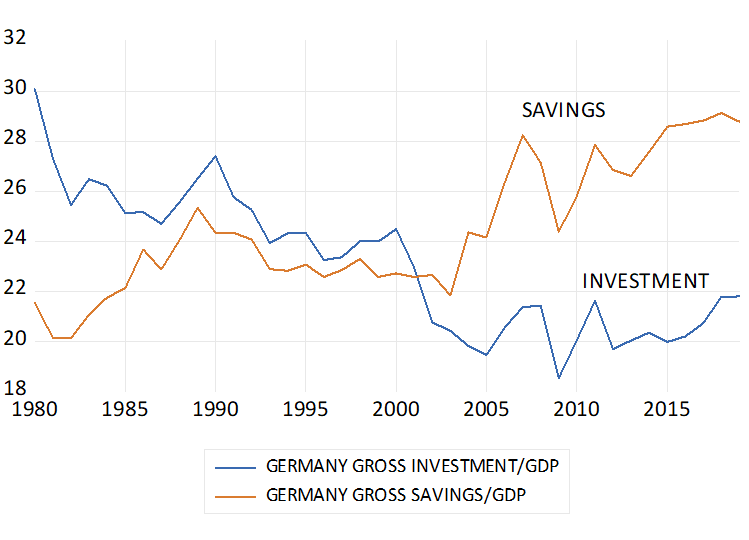

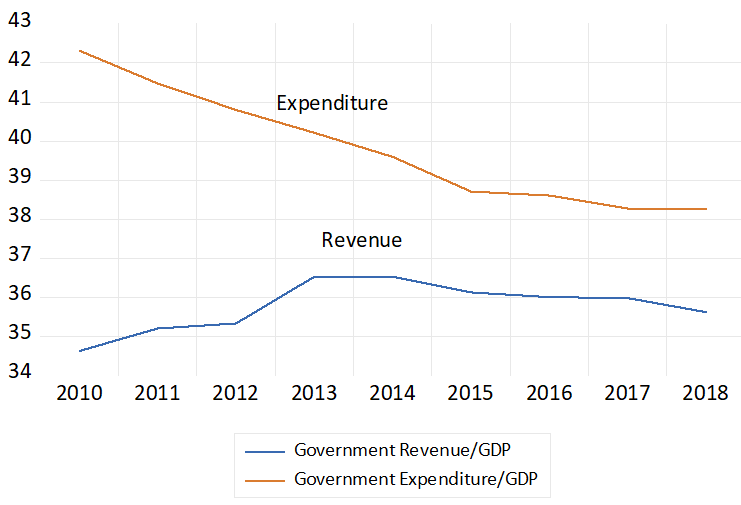

The supply of global savings has in fact held up rather better than the demand for them, helped by an extraordinary increase in the gross savings to GDP ratio in Germany. These savings have increased from about 22% of GDP in 2000 to 30% of GDP in 2018- while the investment ratio has remained at around 22% of GDP. Government budget surpluses have contributed to this surplus of savings in Germany. For advanced economies the share of government expenditure in GDP has fallen from 42% in 2010 to 38% in 2018 while the share of revenue has remained stable at about a lower 35% of GDP. This could be described as global fiscal austerity -post the confidence sapping GFC.

Germany – Gross Savings and Investment to GDP ratios

Source; IMF World Economic Outlook Data Base and Investec Wealth and Investment

IMF – All Advanced Economies – Ratio of Government Expenditure and Revenue to GDP

Source; IMF World Economic Outlook Data Base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Perhaps depressing the demand for capital may be the changing nature of business investment. Production of goods and more so of the services that command a growing share of GDP, may well have become capital light. Investment in R&D may not be counted as capital at all. Nor is intangible capital as easily leveraged.

Lower interest rates have their causes -they also have their effects. They are very likely to encourage more spending – by governments and firms and households. Mr.Trump does not practice fiscal austerity. Boris Johnson also appears eager to spend and borrow more. It would be surprising if firms and many more governments did not respond to the incentive to borrow and spend more and compete more actively for capital. Permanently low interest rates and returns and low inflation may be expected – but they are not inevitable. The cure for low interest rates (high asset prices) might well be low interest rates.