27/09/2018

The economic policy intentions announced by President Ramaphosa last night (26/09/2018) were encouraging if only because it made clear that the President fully understands the imperative of faster economic growth. As indeed he should. It was not obvious that his predecessor cared at all about growth. He had a very different agenda.

The economic diagnosis offered was apposite – for example, to quote the President ‘…Businesses are not struggling with lack of access to cash. It is due to lack of confidence and a dearth of viable investment opportunities that businesses have been reluctant to spend money on fixed capital. These obstacles require policy and regulatory action that provided clarity and raise efficiency …” One might have added—or willing to add working capital that might have been applied to employing more people and improving their capabilities.

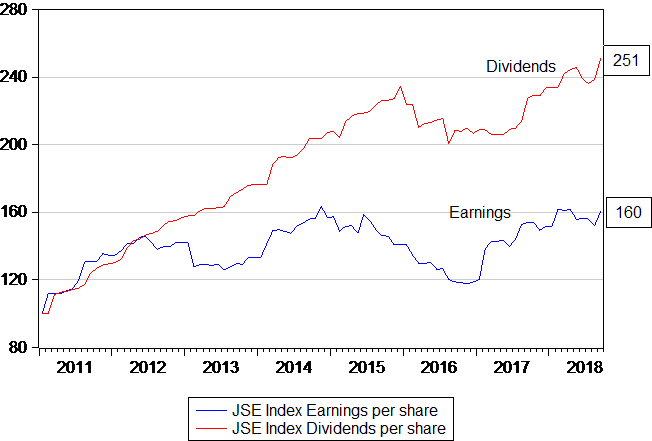

It is important to recognize how JSE listed companies have increased their dividend payments- cash paid out – relative to their after tax earnings in recent years – for want of investment opportunities that offered high enough – risk adjusted returns. Since 2011 dividends have grown 2.5 times while earnings have increased by only 1.6 times

JSE All Share Index Earnings and Dividends per Share (2011=100)

Source; Iress and Investec Wealth and Investment

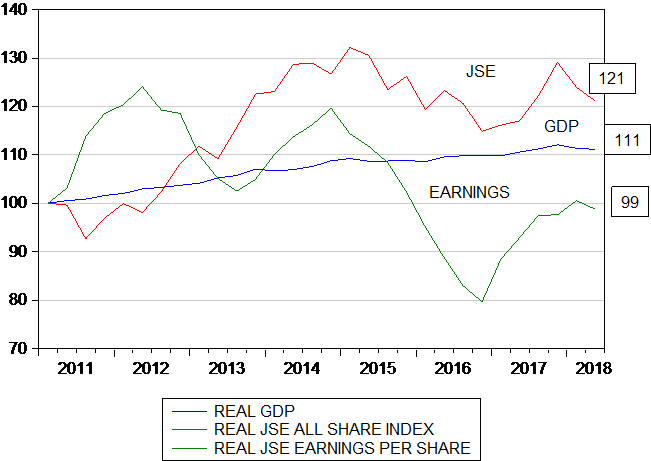

The economy and the share market would have done much better had the cash flow been saved by the listed firms and invested by them in what in more normal times might have proved to be cost of capital beating investments. That is realized returns on capital invested that exceeded required returns of the order of 14% a year. With hind sight shareholders should be pleased that the firms invested as little as they did. Since 2011 the JSE All Share Index, adjusted for inflation, has gained 21%, the real SA GDP is up a dismal 11% (equivalent to an average 1.4% p.a rate of growth, while real JSE earnings have not increased at all over this seven and a half years.

The real JSE compared to the real GDP (2011 =100)

Source; Iress, Stas SA and Investec Wealth and Investment

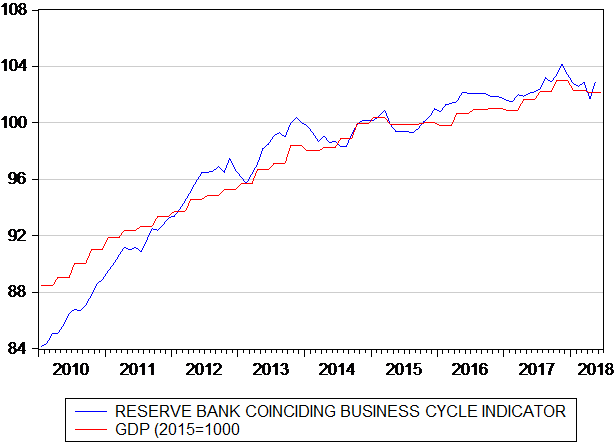

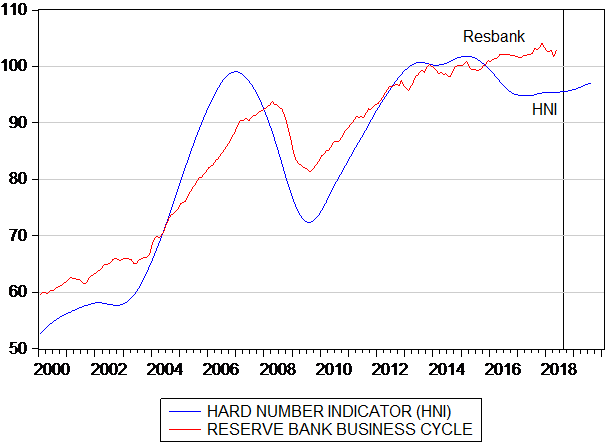

Over recent years the expected returns of SA business have receded with the slower growth expected and realized while the risks to these expected returns have risen. As objectively reflected by the sovereign risk premium demanded of RSA dollar denominated debt. In the fast growth years between 2004 and 2008 (GDP growth averaged over 5% p.a. between 2004 and Q2 2008- ( not fast enough to keep Thabo Mmbeki in his job) the RSA risk premium for five year RSA dollar denominated debt averaged about 0.67% p.a. Since 2014 RSA the yield on SA dollar debt has had to offer on average an extra over 2% p.a on average compared to the yield offered by five year US Treasury Bonds. Put another way returns on an investment in SA assets now have to offer at least an extra 2% p.a in USD to appear worth making.

The South African sovereign risk premium

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

In the service of growth this risk premium has to be reduced, as the President appears to understand. He also appears to recognize that the risks to SA rise and fall with realized growth. The rating agencies remind us constantly of this – and as the currency debt and equity markets also do so. They reacted negatively in response to the disappointing latest GDP growth estimates for Q2 2018. Clearly capital flows in, in response to faster expected growth and out with slower growth expected.

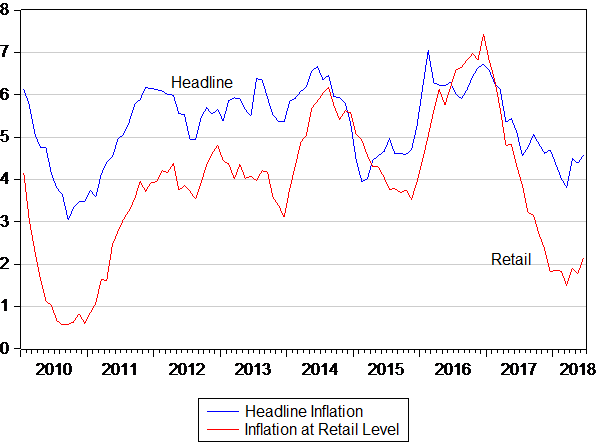

With growth, more capital becomes available on better terms, to support the exchange value of the ZAR. A stronger rand therefore means less inflation, lower interest rates and so further support from the demand side of the economy for growth. A virtuous circle presents itself with growth encouraging policies. One of more growth expected with less inflation given rand strength. As opposed to slower growth- a weaker rand – and so more inflation accompanied by higher interest rates. This has been the vicious circle SA has been trapped in for many years now.

One can express the hope (though the President is well advised not to question the independence of the Reserve Bank nor its judgment) that the Bank fully understands the link between growth, inflation and the exchange rate – over which it has such minimal influence anyway. Three unnamed members of its monetary policy committee (happily not a majority) voted for higher short term interest rates at its meeting last week. With demand as depressed as it is and inflation, outside of regulated prices as low as it is, given the very limited pricing power of firms, one can only wonder at the logic that called for even less demand – that inevitably follows higher interest rates. Perhaps it is the theoretical notion that more inflation expected leads to more inflation- regardless of the state of demand. For which there is no evidence.

South Africa is suffering from both a lack of supply and a want of demand. Fixing the demand side would simply take lower interest rates. Stimulating more demand would also soon bring faster growth now and less – not more inflation. Fixing the supply side of the economy will take longer but would permanently raise the growth potential of the economy.

Our economy could also do with a bit of luck that has been absent since the end of the metal and mineral price super cycle that lasted beyond the Global Financial Crisis of 2008- and only ended in 2011. The SA mining price deflator, converted into US dollars increased by 2.5 times between 2004 and 2011. Prices in USD in early 2016 were about 40 per cent off the 2011 peak, before they turned up again- slowly. Stronger metal prices in USD and more favourable economic trends in Emerging Markets generally would do much to help the rand and the SA economy. These are however global forces over which we have no influence but to which the rand and the JSE and bond yields inevitably react. A mining charter that recognized the trade-offs between growth in output and the distribution of its benefits, beyond those who take on the risks of investment, would be a way of helping ourselves – and is an early test of Ramaphosa realism.