This report has been written with the managers of Remgro, an important Investment Holding Company listed on the JSE, very much in mind. Their managers having received a less than enthusiastic response of their shareholders to their remuneration policies, the company engaged with shareholders on the issue. An action to engage with shareholders that is to be much welcomed.

I have given much thought and written many words explaining why investment holding companies usually worth less than the value of their assets less debt they owned, why in fact they sell at a discount to their Net Asset Value. It occurred to me, as a Remgro shareholder in response to the invitation from the Remgro managers, that my approach could be used to properly align the behaviour of the managers of Remgro with their shareholders. I then engaged with other shareholders in a Remgro webcast and offered to extend my analysis- an offer that was respectfully accepted. This is the result

Applying the logic of the capital market to the managers of companies that invest in other companies

The managers of companies or agencies that invest in operating companies – be they investment holding companies or unit trusts or pension funds –should be judged by the changing value of the share market and other opportunities they invest in. Their task is to earn share market beating risk adjusted returns. They can only hope to do so by accurately anticipating actual market developments. They can do so anticipating the surprises that will move the market one way or another and allocating capital accordingly in advance of them.

The managers of a listed investment holding company, for example a Remgro, a PSG, a Naspers in South Africa or a Berkshire-Hathaway, the most successful of all Investment Holding Companies listed in New York, unlike the managers of a Unit Trust or Mutual Fund, are endowed with permanent capital by shareholders. Capital that cannot be recalled should shareholders become disillusioned with the capabilities of the managers of the holding company. This allows the managers of the HC to invest capital in operating companies for the long run, without regard to the danger that their shareholders will withdraw the funds invested with them- as can be the case with a Unit Trust.

A Unit Trust always trades at values almost identical to the value of the assets it owns, whether funds are flowing in or out or its value per unit has declined or increased- of great relevance to unit holders. This is because these assets can and may have to be liquidated for what they can fetch in the market place.

This is not the case with an Investment Holding Company (HC) The HC cannot be forced to liquidate assets if its shareholders lose confidence in the ability of its managers to beat the market or meet the expectations of shareholders. Therefore the value of the HC shares will go down or up depending on how well or poorly the shares of the holding company are expected to perform relative to the other opportunities available to investors in the share market.

The price of a HC share will be set and reset continuously to satisfy the required risk adjusted returns of potential investors. A lower share price will, other things equal, compensate for any expected failure of the HC to achieve market beating returns through its holdings of assets and its ongoing investment programme. Vice versa a higher HC share price can turn what are expected to be excellent judgments made by the HC, into merely normal risk adjusted returns. In this way through changes in share prices that anticipate the future, the outstanding managers of any company, be it an operating company or a HC that invests in operating companies, that is capable of earning internal rates of return that exceed their costs of capital, will only provide their shareholders with market related returns. Successful companies expected to maintain their excellence charge a high entry price in the form of a demanding share price. Less successful companies charge in effect much less to enter their share registers. Expected returns adjusted for risks therefore tend to be very similar across the board of investment opportunities.

This makes the market place a very hard task master for the managers of a company to have to satisfy. Managing only as well as the market expects the firm to be managed will only provide market average returns for shareholders. And so the direction of the market will have a large influence on share price movements over which managers have little immediate influence. Better therefore to judge the capabilities of a management team by the internal returns realised on the capital they deploy – not market returns.

The managers of the holding company must expect that the operating companies they invest in, are capable of realising (internal) returns on the capital they invest that exceed the cost of capital provided them. That is capable of realising returns that exceed their required risk adjusted returns.

These potentially successful investments may be described as those with positive Net Present Value or NPV. If indeed this proves so, and the managers of subsidiary companies succeed in their tasks, the managers of the HC must hope that the share market comes to share this optimism in their ability to find cost of capital beating investment opportunities. This would add value to the HC whose shares will reflect the prospect of better returns to come from the capital allocated to subsidiary companies in their portfolio. Other things equal, the more valuable their subsidiary companies become over time , the greater will be the value of the HC.

Past performance may only be a partial guide to future performance

Past performance, even a good track record, a record of having found cost of capital beating investment opportunities, may only be a partial guide to future success. The capabilities of the holding companies’ managers to add further value by the additional investment decisions they are expected will be under continuous assessment by potential investors in its shares.

Therefore the market’s estimate of the Net Present Value of the investment programme of the holding company can have a very significant influence on its market value. This value will depend on the scale of the additional investments expected to be undertaken by the HC , as well as the expected ability these investments to realise returns – internal rates of return on capital invested, (irr)– in excess of their costs of capital or required risk adjusted returns.

These expectations will determine the market’s assessment of the NPV of the investment programme. If the irr from the investment programme is expected (by the market place) to fall short of the cost of capital, then the NPV will have a negative value- a negative value that will be in proportion to the value destroying scale of the investment programme. If so the investment programme will reduce rather than add to the market value of the holding company.

The difference between the usually lesser market value of the holding company and the liquidation value of its sum of parts – its NAV – will reflect, we argue, mostly this pessimism about the expected value of their future investment decisions. A lower share price paid for holding company shares compensates for this expected failure to beat the market in the future – so improving expected share market returns.

How managers of the holding company can add to its market value

That an investment holding company may be worth less than the value of the assets it owns is a reproach that the managers of holding companies should always attempt to overcome. They can attempt to do this by making better investment decisions, positive NPV decisions, and convince potential shareholders that they are capable of doing so. They can also add to their value for shareholders by exercising supervision and control over the managers of the subsidiary companies, listed and unlisted, they hold significant stakes in and therefore carry influence over.

They may be able to add to their market value by converting unlisted assets, whose true market value can only be estimated, into potentially higher valued listed assets with an objectively determined market price. They may also succeed in adding value for their shareholders by unbundling listed assets to shareholders when these investments have matured. This would mean reducing the market value (MV) of the holding company but also its NAV and so possibly narrow the absolute gap between its MV and NAV.

Increases in the market value of the listed assets of the holding company adds strength to its balance sheet. Such strength may encourage the managers of the holding company to raise more debt to invest in an expanded investment programme. This extra debt raised to fund a more ambitious investment programme can only be expected to add market value if the returns internal to the holding company exceed its cost of capital. If it is not expected to do so, these investments and the debt raised to fund them will reduce rather than add to NPV. The influence of the NPV estimates on the value of the holding company will however depend on scale of new investment activity compared to the size of the established portfolio. The greater the risks additional acquisitions imply for the balance sheet, the greater will be the influence of the NPV calculation.

A further influence on the value of a holding company will be the costs of maintaining its head office and complement of managers employed at head office. Clearly the net expenses of head office- costs less fees earned from subsidiary companies will reduce the value of the HC.

Our view is that the difference between the value of the holding company and the assets it has invested shareholders capital in is the correct measure of the contribution of managers to shareholder welfare. Hence improvements in the difference between the market value of the holding company and the market value of the assets it has invested in (it may be a negative number) should form the basis with which their managers should be evaluated and remunerated.

A little mathematics to help make the points

In the analysis offered below we support these propositions by identifying, using the logic of algebra, the forces that influence the market value MV as well as the NAV of an investment holding company and the differences between them.

A conventional calculation is made of the Net Asset Value (NAV) of the holding company as the sum of its parts- the sum of the market value of its assets less its net debts.

The NAV of a holding company is defined as

NAV = ML+ MU- NDt …………………. (1)

Where ML is the market value of its listed assets, MU the assumed market value of its unlisted assets less its net debt – debts-cash (NDt) held at holding company level. MU will be an estimate provided by either the holding company itself or independently by an analysis making comparisons of the market value of the holding company with its sum of parts, its NAV. Any difference between the valuation of unlisted assets included in NAV and the market value accorded to such assets by investors in the holding company (a valuation that cannot be made explicit) will have consequences as will be identified below.

The market value (MV) of the listed holding company is established on the stock exchange and can be assumed to be the sum of the following forces acting on its share price and market value

MV=ML+MUm-NDt+HO+NPV………………………… (2)

Where ML is again, as in equation 1, the explicit market value of the listed assets, MUm is the market’s estimate of the value of the unlisted assets that may or may not have a value close to that of the MU included in NAV in equation 1. NDt is the sum of the holding company debt less cash, also as in equation 1, recorded on the balance sheet of the holding company. HO is the cost or benefit to holding company shareholders of head office expenses, including the remuneration of head office management and other employees, less any fees paid to head office by the subsidiary companies for services rendered. HO would usually be a net cost for shareholders in the holding company and if so would reduce the market value of the holding company.

The final force in determining the market value of any holding company is NPV as discussed previously. NPV is defined as the present value attached by the share market to the investment programme the holding company is expected to undertake in the future. The more active this expected investment programme and the larger the programme – relative to the current composition and size of the holding company balance sheet, the more important will be the value attached to NPV. Furthermore it should be recognised from equation 2 that the scale of the investment programme, relative to the size of the established portfolio of listed and unlisted assets will determine how much the dial, so to speak of market value, moves in response to NPV.

Were the holding company managers be expected to undertake investments, be they acquisitions or greenfield projects, that returned more than their cost of capital, this would reflect in a positive NPV. That is to say the greater the (expected) spread between realised and required risk adjusted returns, the greater will be the value attached to NPV for any given (estimated) monetary value attached to the investment programme. However, as discussed previously, the holding company may be expected to be unable to find cost of capital beating investment opportunities. If so NPV would have a negative value and the more the holding company were expected to invest in new projects, the larger would be the negative value that will be attached to NPV. A negative value accorded to NPV would clearly reduce the market value MV of the holding company as per equation 2.

The success or otherwise of the ability of the holding company to add value for its shareholders can be measured as the difference between NAV, net asset value, the sum of parts, and the market value (MV) of the listed holding company or

Value Add= NAV-MV …………………. (3)

It should be noted in the formulation of equation 3, that NAV is presumed to be larger than MV. This is a usual feature of holding companies that are usually worth less than their sum of parts. This negative value is often expressed as a percentage discount of NAV to its market value- as defined below in equation 5.

If we substitute equations 1 and 2 into equation 3 the forces common to the determination of market value (MV)and NAV in equations 2 and 3 that is MU, Net Debt, Debt less cash, cancel out and we can conveniently write the difference between NAV and MV as simply

(NAV-MV) = – (NPV+HO- (MU-MUm))…………………… (4)

It will be noticed that the higher the absolute value of NPV the smaller the difference between NAV and MV. Were however the NPV to attract a negative value the variables on the right hand side of equation 4 would (other things held constant) take on a positive value and increase the difference between NAV and MV. Other forces remaining unchanged, head office expenses and differences between the estimate of the value of the unlisted assets included in NAV and its “true” unobservable value will also narrow the difference between NAV and MV.

The net costs of head office (HO) as mentioned, is likely to have a negative value for shareholders, as would any overestimate of the value of the unlisted assets. If so, to have MV exceed NAV and so for the holding company to stand at a premium rather than a discount to its NAV, the NPV would have to attain enough of a positive value to overtake these other negative forces acting on MV.

A further value add indicated in equation 4 would be to narrow any difference between the value of the unlisted assets included in NAV and its true market value, which cannot be directly observed. Listing these subsidiary companies may well serve this purpose. It will provide them with an objectively determined value that may well exceed its lower implicit value as unlisted companies. If so this can add market value to the holding company.

It would seem clear from this formulation (equation 4) that for those holding companies with an active investment programme, the key to value destruction or creation, the difference between NAV and MV, will be the expected value of its investment programme (NPV) It would seem entirely appropriate for shareholders in the holding company to incentivise the managers of the holding company by their proven ability to narrow this difference and improve VA. Positive changes in VA- that is less of a difference between NAV and MV –that would take an absolute money value that can be calculated continuously – could form the basis by which the performance of the managers of the holding company are evaluated.

We have shown that much of any such improvement in the market value of the holding company and its ability to add value for shareholders should be attributed to improvements in NPV, a variable very much under the control of the managers of the holding company. The reduction of head office costs, or better debt management, or some reassessment of the value in the unlisted portfolio, is perhaps unlikely to significantly move the market value of the holding company.

Were the managers of the holding company able to make better investment decisions and more important perhaps, were expected to make better investment decisions, the market place would reward the shareholders in the holding company accordingly. Though further any contribution they might make to increase the market value of listed companies under their influence or control, could also help reduce the difference between NAV and MV, as we will demonstrate further.

Investment analysts give particular attention to the discount to NAV of the holding company. The notion is that there is will be some mean reversion of this discount and so an above average discount may indicate a buying opportunity and the converse for a below average discount. This discount is defined as

(NAV-MV)/NAV % …………………………………………… (5)

This notion of a (normal) positive discount is also consistent with the notion as indicated previously that the NAV usually exceeds MV. If we divide both sides of equation 4 by NAV and substitute the components of NAV in the denominator we derive the positive discount to NAV as

Disc%=- (H0+NPV-(MU-MUm))/(ML+MU-NDt) …… (6)

As may be seen in equation 6, if the combined value of the numerator is a positive number, then the discount attains a negative value- that is the market value of the holding company would stand at a premium to the sum of its parts – Berkshire Hathaway might be an example.

Clearly any change that reduces the scale of the numerator (top line) or increases the denominator (bottom line) of this ratio will reduce the discount. Thus a less expensive head office (HO) or an increase (less negative) in the value of future business (NPV) will reduce the discount. (These forces represented in the numerator of equation 6 are preceded by a negative sign. As per the denominator, any increase in ML or MU or a reduction in net debt will reduce the discount.

However while reducing the discount is unambiguously helpful to shareholders and will be accompanied by an improvement in NPV, this will not always or necessarily be the result of action taken at holding company level. Any increase for example in the market value of the listed ML or unlisted investments MU will help increase the absolute value of the denominator of equation 6 and reduce the discount and add NPV. But such favourable developments may have everything to do with market wide developments that influence ML or MU and have little to do with the contributions made by the management team at holding company level.

Thus it is the performance of the established portfolio relative to some relevant peer group rather than the absolute performance of the established portfolio should be of greater relevance when the performance of the managers are evaluated. These influences on the value add might be positive or negative for the value add for which management should not be penalised or rewarded.

It would therefore be best to measure the contribution of management by a focus on the underlying drivers of NPV seen as independent of the other forces acting on the market value of the holding company. Furthermore the focus of the managers of the holding company and their remuneration committees should be on recent changes in the absolute difference between NAV and MV and not on the ratio between them.

Unbundling may prove a value added activity – the interdependence of the balance sheet and the investment programme- for which the algebra cannot illuminate.

Unbundling listed assets to shareholders might well be a value adding exercise. It would simultaneously reduce both NAV and MV, but possibly reduce the absolute gap between them. Because such action could illustrate a willingness of the management of the holding company to rely less on past success and to focus more on the merits of its on-going investment programme. Reducing the size and strength of the holding company balance sheet may make the holding company less able and so less likely to undertake value destroying investments. An improvement in (expected) NPV and so a narrowing of the difference between NAV and MV might well follow such an unbundling exercises to the advantage of shareholders. That is helpful to shareholders because even as the absolute size of the holding company’s NAV and MV decline, the difference between them may become less negative- even become positive should MV exceed NAV

Conclusion

We would reiterate that the purpose of the managers of the holding company should be to serve their shareholders by reducing the absolute difference between NAV and MV and be rewarded for doing so. A focus on this difference, hopefully turning a negative number into a (large positive one) would be highly appropriate to this purpose.

Appendix

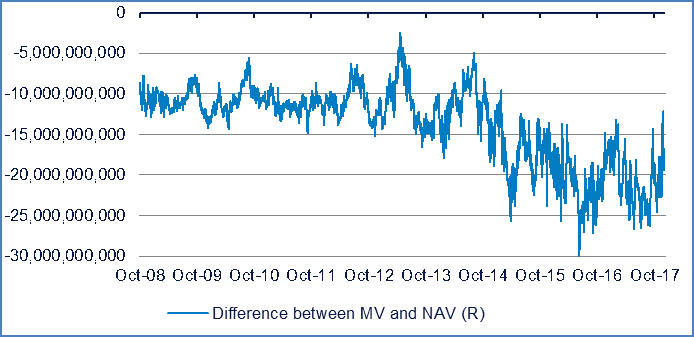

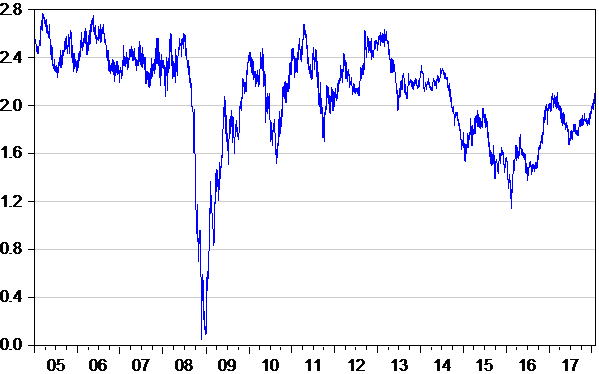

Remgro: chart reflecting estimated difference between the market value of Remgro and our calculation of its net asset value

Source: Investec Wealth & Investment analyst model

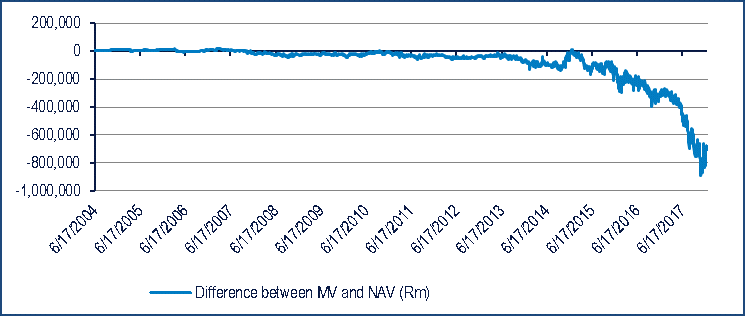

Naspers: chart reflecting estimated difference between the market value of Naspers and our calculation of its net asset value

Source: Investec Wealth & Investment analyst model