The very large weighting of Naspers in leading indices like the JSE Swix and the JSE All Share Index has major implications for active and passive investors alike. Investors need to be aware of what this means for the risk attached to their portfolios.

The original reason for constructing a stock exchange index was simple: to provide a statistic that summarised the price performance of the average company listed on a widely followed stock exchange. The calculation of such an average or index is supposed to represent the general direction of the equity market.

The most famous and oldest of the indices that tracks share prices on the New York Stock Exchange, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), simply aggregates the US dollar share prices of the 30 largest US companies. The higher the prices of the individual shares included, the higher the DJIA and vice versa. The S&P 500 was introduced later and has become the most important of the global indices. In contrast with the DJIA, the S&P 500 tracks the market value of the 500 largest companies listed on the New York stock exchanges. The share price moves of the largest companies carry the most weight in the index and move the index proportionately.

Indices that attempt to summarise equity market performance, however, have much more than simply an informative role. They are also widely used to measure the ability of fund managers who actively manage their share portfolios and compete with other managers for assets to manage. Relative, as well as absolute price performance and returns, matter to both fund managers and their clients.

The performance (total returns in the form of price changes plus dividend income) of the funds they manage are not only compared to those of their rivals, but also to some relevant equity index. The ability to generate returns ahead of the benchmarks – the returns (theoretically) generated by the index (positive or negative) – becomes their measure of success or failure. Conventional wisdom now dictates that index-beating returns, beating the market (after fees), is the only reason for active management. We will show why this is incorrect.

A passive approach

Because of the difficulty that the average equity fund manager faces in trying to perform better than the index, there has been a large move to so-called passive equity investment strategies. Investors simply track some index by dividing their equity portfolios in exactly the same proportions (weights) as the shares included in the index.

Index tracking funds (under the banner of the so-called exchange traded funds or ETFs) have been created in large numbers by different fund management houses to facilitate such an investment strategy. This process generates no more or less than index-equivalent returns for the investor. The advantage for the investor is that since no knowledge or experience of the market place is needed – only a suitably programmed computer – the fees charged for the service (usually measured as a percentage of the assets under management) can be far lower than the fees typically paid for actively managed portfolios. These latter fees are charged to cover the higher costs of active managers, for example the salaries of the stock pickers and their analysts, as well as the trading and marketing costs incurred by the firms.

The ETFs and their originators and managers are therefore taking full advantage of highly efficient and competitive equity markets, without contributing to the process of price discovery. It is this efficiency in processing information about companies and the economic and political forces that will influence their future profitability (and their current value) that makes the share market so difficult to beat. Such information comes without expense for the passive investor.

Another expensive responsibility incurred by active shareholders is the surveillance of the managers of the companies in which they invest client wealth. This responsibility and the accompanying costs are largely avoided by passive investors. Good corporate governance demands that shareholders cast their votes on corporate actions by exercising proper diligence, which has a cost. Engaging actively with company managers is essential for active investors but not for index trackers.

The index trackers are free riders on the investment bus, paid for by others. The proportion of funds that would have to be actively managed to make for a well-informed, efficient marketplace and to keep the investment bus rolling cannot be known with any degree of certainty. If all investors simply followed rather than led, the market would be full of valuation anomalies, from which only a few active investors could become fabulously wealthy by exploiting the valuation gaps.

The relevance of risk

Prospects like these are what encourage active investors to take risks. Think of hedge fund managers who take large risks in exchange for prospectively (not always realised) large returns. They also add helpful liquidity to the market that facilitates trading activity by risk averse investors. It is the expected distribution of returns, the small chances of a big win on the markets and the potential to achieve long run returns sustained well above average market returns that explains some of the preference for active managers. A select few of these (though we never know which few) will always beat the market by a large and sustainable margin.

This raises an all-important issue. Investment decisions and the make-up of investment portfolios are not determined only by prospective returns. The risk attached to such prospective returns is at least as relevant for the average wealth owner saving for retirement or a rainy day. This is the risk that the portfolio can lose as well as gain value. Stock market indices and the ETFs that track them can be more or less risky, depending on their character and composition. An essential requirement of a low-risk equity portfolio, actively or passively managed, is that it should be well diversified against risks that individual companies are exposed to.

This is achieved by spreading the portfolio among a large number of shares, none of which should account for a large proportion of the portfolio. The threats to the value of a share of a company that comes from adverse circumstances beyond the control of all company managers – i.e war, revolution, taxation, expropriation, regulation, inflation and financial crises – can only be mitigated by diversifying the wealth owners’ total portfolio across different asset classes, such as bonds, cash or real assets – or different jurisdictions. Index-tracking ETFs can simulate a particular equity market or well traded sector of it. But designing an optimal, risk-aware total portfolio – how much equity or other risks a wealth owner should assume – calls for more complicated considerations.

An important consideration for any investor tracking some equity market index is the issue of how well diversified the index being tracked is. A further consideration is which equity markets should be tracked given their very different risk profiles and how they are constructed.

The S&P 500 is very clearly well diversified against US company specific risks. The JSE All Share Index, by contrast, is not well diversified, nor is the JSE Top 40 Index nor the JSE Shareholder Weighted Index (Swix), which has largely superseded the other JSE indices as the benchmark for measuring the performance of SA equity managers. The Swix is weighted by the shares of the company registered by the JSE itself, as opposed to shares registered for transfer on other exchanges where the company may also have a primary or secondary listing. The larger the value of the shares registered by the JSE (Strate), the larger the weight that company will be allocated in the Swix. It should be understood as a measure of the proportion of the shares registered for transfer in SA, not necessarily of the share of the company owned by South Africans.

How diversified is your index?

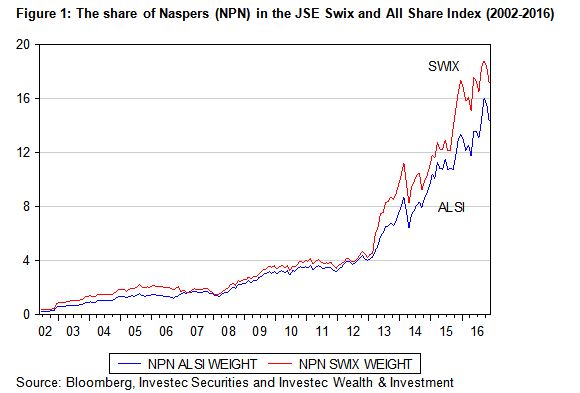

The largest company currently included in the S&P 500 Index is Apple, with an S&P 500 Index weighting of only about 3%. The largest 100 of the S&P 500 account for about 60% of the index. In strong contrast, the largest company included in the market capitalisation-weighted JSE All Share Index in November 2016 was Naspers, with a weight of 17.14% in the Index. The next largest company included was British American Tobacco, with a much smaller weight of 4.31% followed by Sasol with 4.08%. The largest 10 companies included in the All Share Index now account for as much as 42.6% of its weighting – it’s clearly a much less diversified index than the S&P 500. Until its recent takeover, SABMiller was accorded a large weight in the All Share Index and the other leading indices. It is no longer represented and its new owner, AB Inbev, while already listed on the JSE, at the time of writing had still to make an appearance in the indices. The weights in the Swix have become similarly lopsided as we show below in figure 1. The weight of Naspers in the Swix is now even larger than that accorded to it in the All Share Index.

The weight of Naspers in the JSE indices has risen automatically with the extraordinary and persistent increases in its share price. Naspers shares are also all registered on the JSE, though foreign investors hold a large proportion of the company. As important for increasing the weight of Naspers in the indices has been the near stagnant value of resource companies that once had a very large weight on the JSE, but whose valuations have increased very little over the same period.

From mining to media

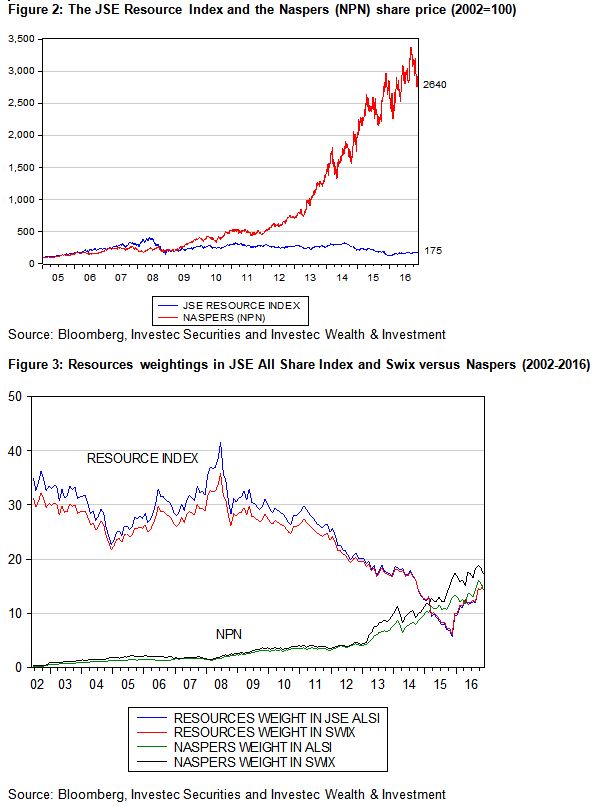

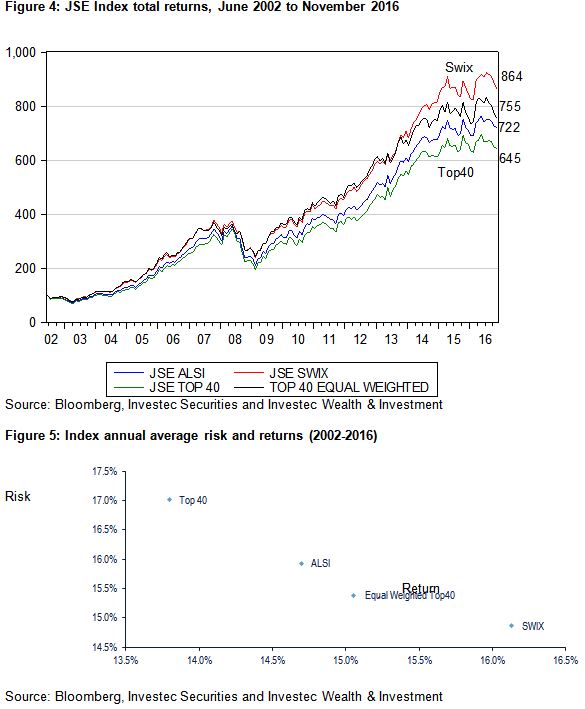

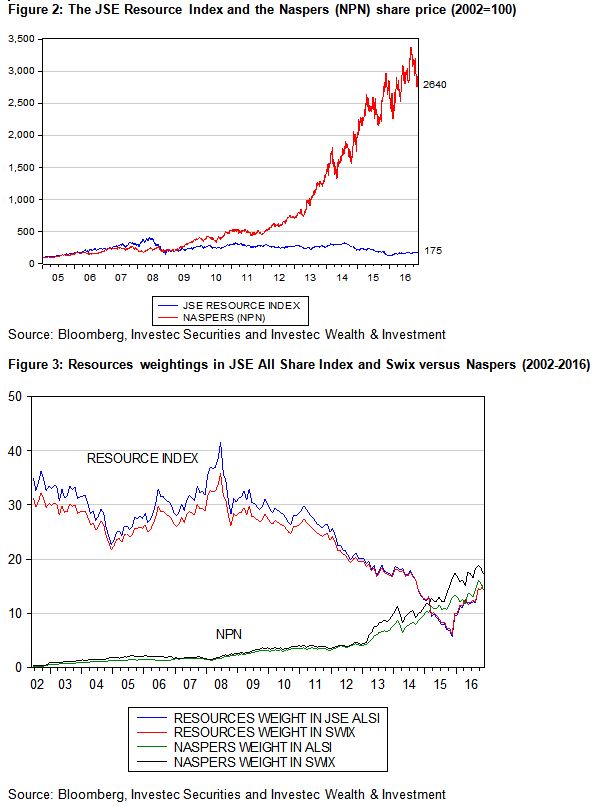

In figure 2 we compare the Naspers share price with that of the JSE Resources Index. The Naspers share price has increased 26.4 times since June 2002 while the JSE Resources Index has not even doubled over the same period. In figure 3 we show consequently how the weight of resources in the JSE All Share Index has declined from over 40% in 2008 to about 15% today, a lower weighting than Naspers on its own. The Swix reveals a very similar pattern, according a very high weight and importance to the Naspers share price moves and much less importance to resource companies in the direction the index takes (and so any ETF that tracks the JSE All Share Index or Swix).

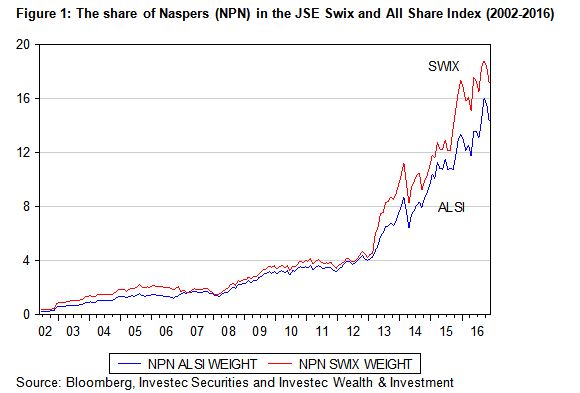

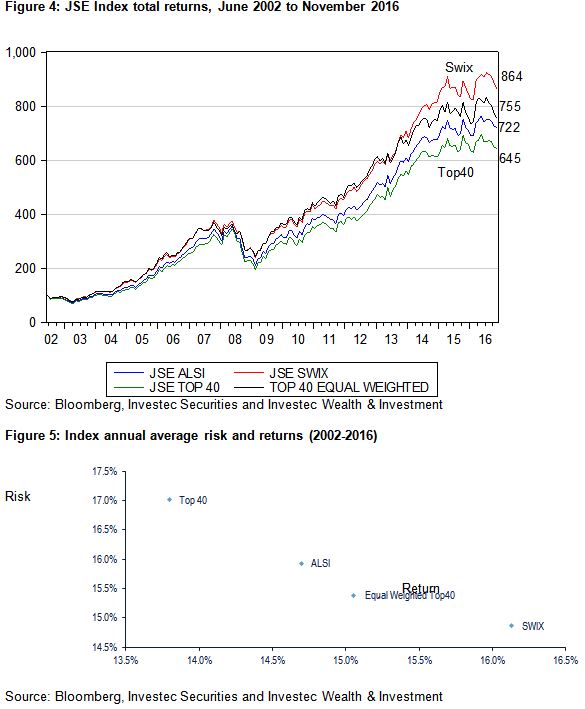

It is the rising Naspers share price and its growing and larger weight in the Swix that has made the latter the best performing of the local indices over the past 14 years. The differences in performance are significant. R100 invested in the Swix in 2002 with dividends reinvested (before fees and taxes) would have grown to R864 by November 2016. The same investment in the JSE Top 40 would only have realised R645, with the All Share Index and an equally weighted index of the 40 top companies performing somewhat better. Not only did the Swix deliver higher returns, but it did so with less volatility than the other indices, thanks to Naspers (see figures 4 and 5 below).

Clearly, choosing the right index to represent and track the JSE and measure the performance of active managers is an important decision for investors or their advisers to make. All indices are not alike and some can be expected to deliver returns with much greater risk or volatility than others.

The major JSE indices that might be used to deliver market equivalent returns by some tracker fund or others are not suitable for diversifying the specific company or sector risks that investors tracking the index will be exposed to. Naspers carries far too much weight and therefore exposes index-tracking investors to much more danger than would be appropriate for any risk averse portfolio. The same criticism could have been made of the composition of the JSE indices in 2008: they were too exposed to the specific risks that faced resource companies. Investing over 40% of an equity portfolio in resource stocks – with their well known dependence on highly unpredictable metal prices – is not something a risk averse investor would want. The same argument could be made of a current exposure to Naspers: investing up to 20% of a portfolio in one company would be regarded as highly unwise.

Wise and risk averse active managers presumably would not have allocated 40% of their portfolios to resource companies in 2008. And, they would have been much more likely to have outperformed the indices over the subsequent eight to nine years as resource valuations fell away. They would also have done even better with a larger-than-index weight in Naspers. But the risk conscious fund manager would have had to become ever more cautious about exposure to Naspers after 2013, when its weight in the index began to exceed 10%. Prudence would suggest that no more than 10% of any equity portfolio should be invested in any one company.

Given this, along with the current 18% plus weight of Naspers in the leading SA indices, active managers are therefore much more likely to underperform the index when Naspers is outpacing other stocks, as has been the case until recently. Conversely, they would outperform should Naspers lag behind the other stocks included in the index. The case for or against active management in SA should not have to depend on the fortunes of one company.

Judging the performance of a fund manager in South Africa by reference to a very poorly diversified Index like the JSE All Share Index or Swix would not be an appropriate exercise. Realised returns should always be compared to the risks that were taken to achieve those returns. The task of the active manager is not simply to aim at the highest returns for their clients, they should also be managing risk.

Recognising the risk tolerance of their clients and allocating assets and planning savings accordingly is a large part of a fund manager’s duties. This is even more important when the market (index) carries identifiable and unjustifiable risk as the JSE indices have done and continue to do. Even when the active investor has not beaten the market, the advice offered can be very valuable.

There is incidentally no risk when calculating past performance. Risks apply only to expected performance – not to known past performance. Investing in an index tracker is not a decision that can be made passively because such advice is not easily provided by a robot and is worth paying extra for, or ignored at the investor’s peril.

Note: I am indebted to Chris Holdsworth of Investec Securities who painstakingly undertook all the Index and return calculations that are used and represented in this report. All the indices used in the study are dynamic ones representing the indices and the sector and share weights in them, as they occurred over time.