Interest rates, exchange rates and the JSE (in US dollars) before and after the Trump Shock: all have been good for the SA economy. Now it’s over to the Reserve Bank

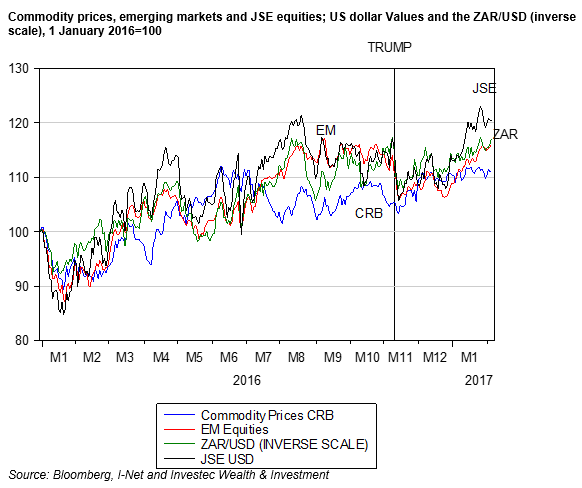

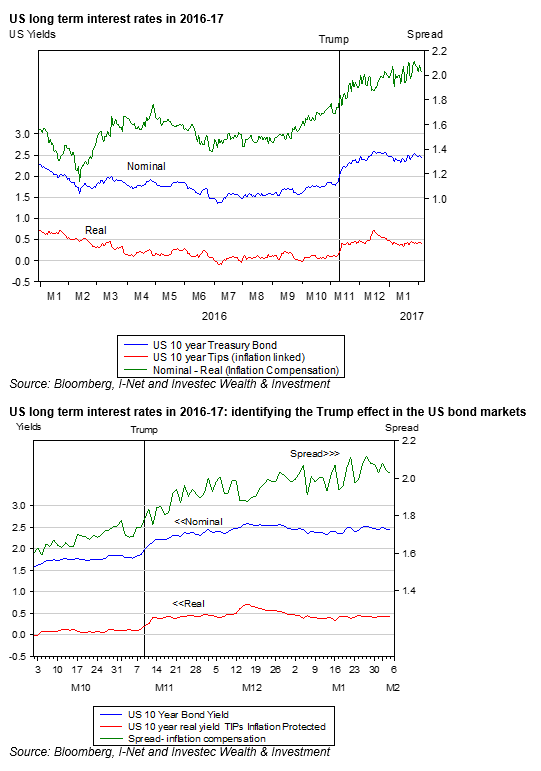

US 10 year yields, nominal and real, after declining to very low levels by mid-year 2016, then began to rise. The Trump election added further momentum but, as may be seen, long term interest rate levels in the US have largely stabilised at higher levels in 2017.

Nominal rates are now about 100bp higher than they were in mid-2016 while real rates have gained about 50bp from approximately zero rates in mid-year. Accordingly the spread between the nominal and real yields that offer compensation for the inflation risks that holders of nominal fixed interest bonds assume, has widened. This indicated more inflation expected over the next 10 years, of the order of 2% p.a. The higher real rates indicate increased real costs of capital – a sign of faster growth expected and the increased demands for capital that come with faster growth. Thus the US bond market indicates that both more inflation and faster growth are now expected in the US. The rising US equity markets have regarded improved earnings growth prospects as more than adequate to off-set higher discount rates.

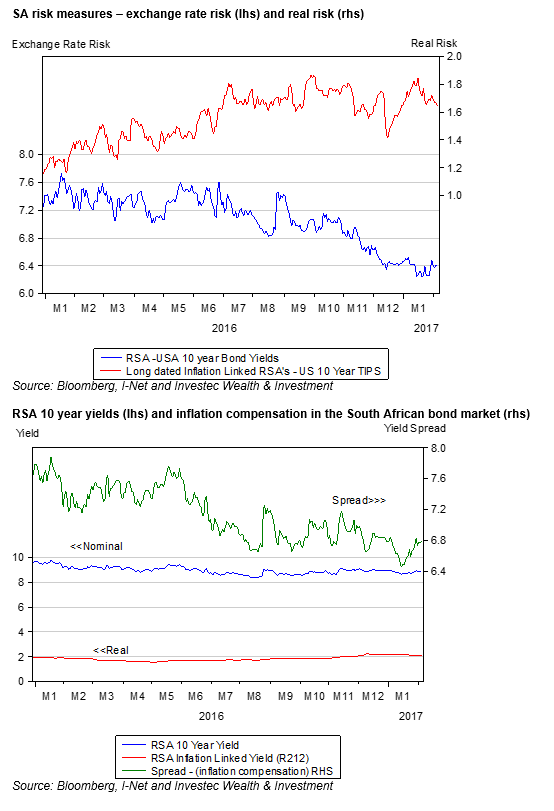

Long term interest rates in SA have taken a somewhat different course to those in the US. As may be seen below, RSA 10 year yields have edged lower while real yields have edged higher. The spread, indicating inflation expected over the following 10 years in the RSA bond market, has generally moved lower, from a very high near 8% in early 2016, to current levels of about 6.5% indicating still elevated inflationary expectations.

That longer term rates in the US have moved higher and equivalent rates in SA lower means that the spread between RSA and US rates have declined. This spread may be regarded as a SA risk premium, the extra yield required to compensate for the expected weakness of the rand, and equivalent to a forward exchange rate.

The difference in real yields may be regarded as the extra, after inflation yield required by foreign investors to compensate them for all the risks associated with investing in SA assets. As may be seen in the figures below, SA risk, that is the rate at which the rand is expected to depreciate against the US dollar, has declined as the rand strengthened, while the real risk premium offered to investors in SA has remained largely unchanged.

The faster the US and global economies are expected to grow the higher the expected rates in the US. But faster growth is helpful for commodity prices and emerging market currencies and equities and their profitability and reduces the risks associated with investing in emerging market economies.

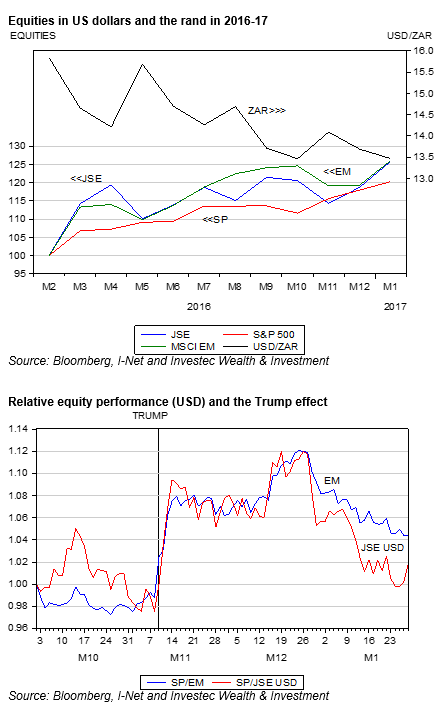

Evidence of these helpful trends is clear enough, as may be seen in the figure above that graphs the similar responses of commodity prices, emerging market and JSE equities over the past year as interest rates have risen in the US.

What remains for the SA economy to benefit from improved outlook for the global economy is for the Reserve Bank to reduce its anxiety about the prospect of higher interest rates in the US and focus its attention on the downside risks to the real SA economy, rather than the upside risks to the rand and inflation, and to lower short term interest rates accordingly (President Zuma naturally permitting – and what he permits by way of his cabinet choices will be known this week).

*The views expressed in this column are those of the author and may not necessarily represent those of Investec Wealth & Investment