For SA Jewish Board of Deputies, The Big Immigration Debate- what type of immigration policy should South Africa adopt? With remarks from Naledi Pandor, Minister of Home Affairs, Mamphela Ramphele, Cris Whelan, Rapelanf Rabana and myself

Cape Town, 31st October 2013

Why immigrants are good for economic development

Increased supplies of any valuable resource, natural resources, fertile land, convenient waterways, minerals etc as well as of labour or capital are helpful to an economy- they bring more output and incomes, including revenue for the Government. Immigrants not only add to the potential supply of labour they can add to the supply of capital as well as of enterprise. By capital one means not only their savings but of more importance the value of the skills they have acquired through education or training and through on the job learning in their home countries.

Immigrants are a self selected group – they have get up and go- a willingness to escape poverty or the lack of opportunity at home. They are therefore likely to have an above average degree of enterprise and risk tolerance.

The (present) value of their skills – realised in the production of goods and services – and represented by the employment benefits they earn – over and above those earned by unskilled workers with almost only their energy to offer – is described by economists as human capital. It can be calculated in a very similar way in which the present value of some flow of income from a machine or building can be estimated. Human capital is created through a process very much like that undertaken when more tangible capital, physical plant and equipment is added to the capital stock. It typically takes a willingness to save , to give up the current consumption of goods and services – while undergoing training or an education – for the sake of increased incomes and consumption in the future. In other words individuals save to invest in their skills the returns from which will be enjoyed over time in the form of extra income and additional consumption that comes with higher incomes. The returns from investing in human capital- the extra income associated with extra years of education- can be very high indeed which is why such savings and investment activity is eagerly undertaken.

Often this training and education, the generation of human capital, will be highly subsidised by governments- that is by taxpayers hoping for a return on their contributions in addition to that realised by the better skilled individuals themselves. That is to say a better skilled or educated population generates positive externalities for the community at large.

The case for encouraging the immigration of skilled labour is for the host society to benefit from these externalities. That is to gain benefits beyond those realised by the migrants themselves, when given the opportunity to apply their skills or enterprise in the economy to which they have migrated .

Migration has income (output) effects but also influences income differences.

The extra supply of migrant skills or energy will have an influence on not only on total output (GDP) and incomes but also on real or relative employment benefits. That is on the relative or comparative incomes of the better off who benefit from human capital and the less well off who command very little of it. An increased supply of skilled workers will tend to reduce their scarcity value. By the same token an increased supply of skills will increase the relative scarcity of unskilled labour. The more capital, including the more human capital available to an economy, the higher will tend to be the demand for and the so the real value of lower paid, less skilled labour

It seems clear that the value (real wages earned) earned by relatively unskilled labour local labour will benefit from an increased supply of human as well as physical capital. The more capital made available to an economy relative to its supplies of labour, the greater the scarcity of labour, the more demand for such labour, the more productive such labour and so the greater will be its rewards as employers compete for their services. Workers with equal strength have long commanded a higher scarcity value in the US compared to China because of the relative abundance in the US of natural resources as well as of capital. Adding capital is very helpful to those with only their strength to offer employers – it is less obviously welcome by those advantaged with skills, human capital, who might resent the competition and the pressure on their employment benefits.

The political resistance to the migration of skilled workers would most obviously come from the economically advantaged, those with valuable education and skills – not those disadvantaged for want of education or training. The political resistance to the migration of unskilled labour will surely come from the relatively disadvantaged through lack of skills. Those in possession of scarce skills or capital more generally will have a strong economic interest in encouraging unskilled migrants. Less expensive labour intensive services for the homes of the better off, is an obvious benefit.

South Africa’s immigration practice has by design or practice been helpful to the advantage South Africans- and not helpful to the poor.

South Africa’s policies with respect to immigration- allowing by accident or design relatively free access for unskilled labour – from Zimbabawe or elsewhere in Africa- while by accident or design – raising barriers to the migration of skilled labour have surely been helpful to the those advantaged with skills or capital while being generally unhelpful to established unskilled labour.

Potential workers (unskilled and skilled) will migrate from regions with lower real employment benefits to those that offer more, if opportunity presents itself. By so doing all other things remaining the same they will add to the scarcity of labour in the home region and reduce it in the host region. Employers in the host region will welcome more labour and those in the home region will find their employment costs uncomfortable. The flow of people as the flow of capital is usually a response to growth and so the prospect of higher returns. Faster growing nations and regions attract workers and capital while slow growing regions repel labour and capital.

Push from conditions in the home country rather than the pull of an improved labour market in the host country can drive the flow of migrants

However there is the possibility of push rather than pull dominating outcomes in the labour and capital markets. Famine or failed nations can drive people and their savings away and help to depress returns in the host country that if growing slowly will find it more difficult to be hospitable. The case of people migrating away from Zimbabwe towards SA is a case more of push than pull. The case of skilled South Africans migrating away from the UK or the US after the Global Financial Crisis and its impact on employment opportunities is a further case of push more than pull.

South Africa may have made it difficult for firms to hire skilled foreigners. It has not done much, fortunately for the sake of the economy, to inhibit the flow of skilled South Africans back home. The numbers of returning South Africans reversing the brain drain has been very impressive. I have been given the number of returning professionals and managers by employment agency Adcorp- who are in a good position to know the details – as a very impressive 370,000 skilled migrants who have returned to SA since 2009. In recent years the SA economy has managed to do without attracting skilled foreigners in magnitude by absorbing large numbers of its own Diaspora. I will give some sense of the importance of these returnees for the economy at large below.

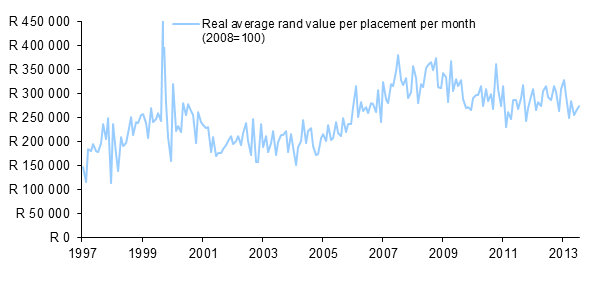

The impact on the remuneration of the professional classes in SA of this return is demonstrated by this figure shown below, also obtained from Adcorp. As may be seen the average real wage at which they were able to place young professionals or managers doubled through the SA economy boom years between 2003 and 2008 from R150,000 p.a in 2003 to R350,000 in 2009. To convert these salaries to 2013 money multiply by about 1.3 times. In recent years these salaries at which Adcorp have been able to place their clients has declined significantly. Furthermore the number of these placements by Adcorp has declined by as much as 60% No doubt in the face of the increased supply of skills provided by the returnees. Clearly South African firms hiring skilled labour could have benefitted from access to immigrant skills before 2009 – just as they have benefitted from migrant skilled labour since.

Source; Adcorp, Private Communication

Putting SA skilled migration trends in context

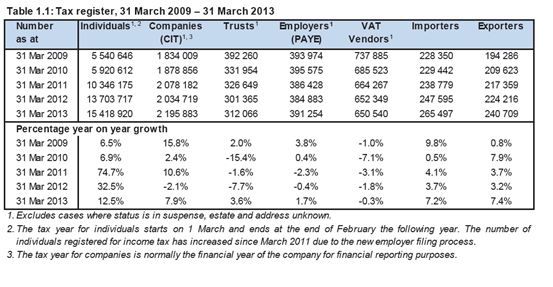

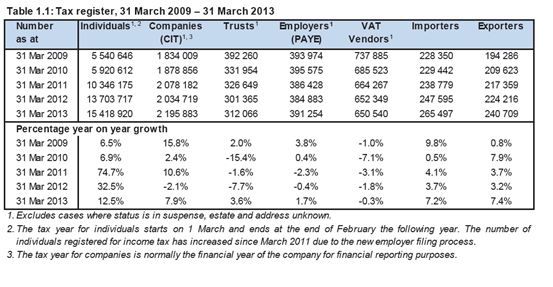

To give a better idea of the importance of 370 000 skilled entrants to the SA labour market we can refer to data supplied by SARS in their recently issued, 2013 Tax Statistics, that can be found on the national Treasury web site. SARS reports 15 418 920 individuals as registered for PAYE. Not all potential income taxpayers earn enough to have to pay income tax (more than R60,000 p.a. in 2012) These numbers of registered taxpayers have increased dramatically in recent years as firms were forced to include all workers in their tax filings from 2011. (See table below)

Of the 15.4m registered workers some 5.1m actually paid income tax. 3.2m of these taxpayers earned a taxable income of more than R120,000 – perhaps qualifying them as skilled. These 370 000 returning migrants therefore represent more than 10% of the skilled labour force. It will be of interest to note that 338,724 taxpayers reported taxable income of more than R500,000 in 2012, 73,250 taxpayers enjoyed taxable income of more than R1m in 2012 of whom 16,952 earned bwtween R2 and R5 million while a mere 2,787 taxpayers reported taxable income of more than R5m.

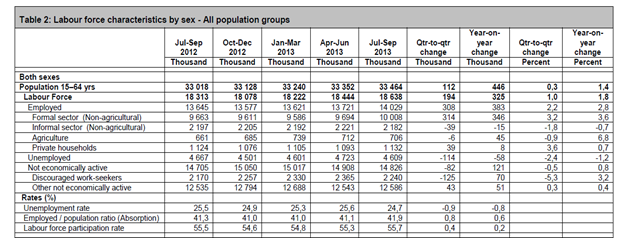

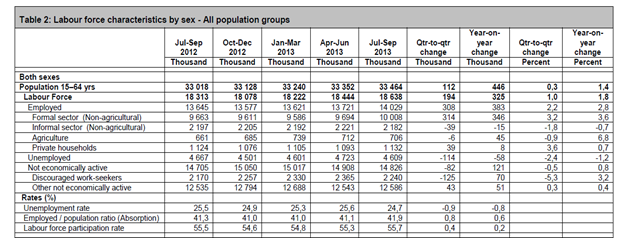

What makes these statistics especially interesting is that the 15.4 million taxpayers registered with SARS compare very favourably indeed with the employment numbers recorded by Stats SA in their Quarterly Labour Force Survey that records employment and unemployment from a survey of households . Stats SA reports a labour force of 18m of whom 10m only are estimated as formally employed. (See below)

Source; Stats SA QLFS

Such grave dissonance between the numbers of employees recorded by SARS and by Stats SA needs to be urgently resolved if we are to say anything useful about the SA labour market and the impact of immigration and migration on it.