Published in Investec Wealth and Investment Private View Quarter 2 2013

There is perhaps only one observation one might make with great confidence about the value of a firm: that over the long run its market value will be aligned to its economic performance. The better the realised performance, the more valuable the firm or a share in it will be.

In the long run economic fundamentals account for share values

There is perhaps only one observation one might make with great confidence about the value of a firm: that over the long run its market value will be aligned to its economic performance. The better the realised performance, the more valuable the firm or a share in it will be.

The problem for the analyst or investor is that the market is always attempting to value the expected rather than the realised performance of a company. These expectations can change from day to day, while it is only over the very long run that performance and its valuation will converge in an understandable way. The market does however provide consistent clues about the expectations implicit in market valuations. These clues then allow the investor to make judgments about the realism of these expectations of performance. They may be judged too optimistic (therefore providing reasons to lighten exposure to the market) or too pessimistic (making a case for increasing exposure to equities, that is for taking on more risk).

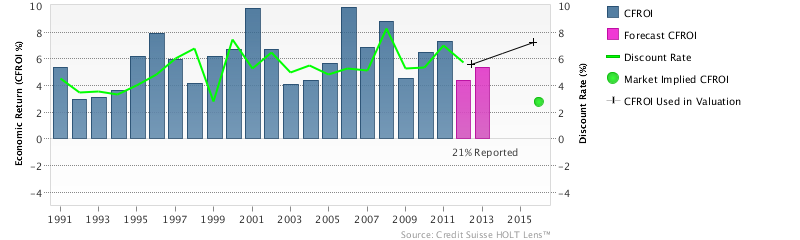

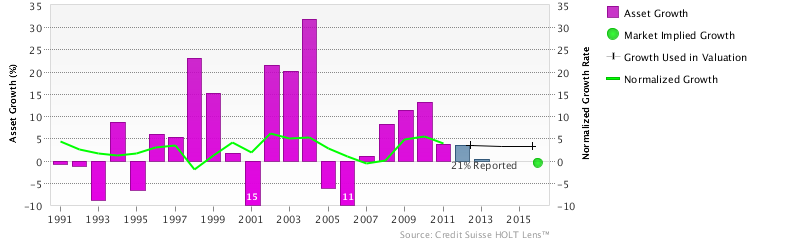

A firm’s economic performance might be calculated using a variety of metrics: accounting earnings per share (after interest and taxes paid) would be the most obvious measure of performance; dividends per share or operating profits might serve better as a measure of business success or the lack of it; so might cash flow – so called EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) – be preferred as a measure of the economic performance of a company; free cash flow (that is cash flow after investment activity) might indicate how well the company is doing.

These performance measures might best be normalised to exclude extraordinary temporary additions to or subtractions from bottom line accounting earnings. This would give rise to the so called headline earnings reported by JSE listed companies or even normalised headline earnings reported by some companies. The deepest insights into how well a company is performing are most likely to be found in measuring the cash flow return on capital (the return on the cash invested by the firm, suitably adjusted for inflation).

When we aggregate the performance of all the firms that make up a stock market, we find that all of these different measures of performance prove to be highly correlated. They will all tell a very similar story about how well the firms that make up the stock market have done over time.

Expected rather than past performance accounts for the short run behaviour of the market place

The problem for the investor is that while realised performance will be decisive in determining the value of a company over the long run, the market place does not sit by patiently waiting for economic performance to unfold. The day to day value of a company or the share market is determined by expected rather than past performance. And as investment advisors are constantly obliged to remind their clients, past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance – even though it may be the only useful guide available.

Future economic performance implicit in current market values can as easily be overestimated as underestimated. If such estimates are proven (by subsequent events) to have been too optimistic, market values will tend to fall into line with disappointing economic outcomes. If the estimates of performance are too pessimistic then share prices will tend to rise and thus fall into line with the unexpectedly good economic outcomes.

Prices fall in line with performance – or performance catches up with prices

In any longer run view of the relationship between values and performance, either prices will fall into line with disappointing performance or unexpectedly good performance will drive prices higher. In the long run prices and performance will track each other.

The environment also matters – as reflected in the discount rate applied to future performance

There is a related issue when the value of a firm or a market has to be determined. This is the rate of discount which should be applied to expected performance, measured as a flow of earnings, dividends or free cash flow over time. Clearly future expected benefits from the ownership of an asset or firm are less valuable than current benefits gained from owning any asset or a share. Any market value can be logically regarded as being the result of a present value calculation. A similar calculation will be made by any firm contemplating capital expenditure. Future expected benefits have to be discounted to derive their present value.

This discount rate wlll be very much influenced by interest rates prevailing in the market place. Investing in a share is an alternative to investing in cash or short or long dated government bonds paying a fixed rate of interest with a certain money value. When investing in the shares or the debt of companies, a risk premium will be added to these interest rates to compensate for risk of default or failure.

But it is not only the risk to the firm that will be taken into account when values are estimated. It is the risks posed by government to the economic outcomes for firms and share owners that will be reflected in interest rates offered by government borrowers. For example the risks of higher or lower inflation will be revealed in these minimal interest rates, as will risks that government will tax interest income more heavily or will come to rely more heavily on debt than tax revenues to fund additional expenditure.

Furthermore interest rates will also rise or fall in response to a real shortage of savings. If the demand for savings or capital strengthens, from firms and the government itself, then real, after (expected) inflation interest rates will rise and vice versa. The greater the competition for capital, the higher will be real interest rates, and so the less valuable will be the present value of an asset as benefits are discounted at a higher rate.

Good news and bad news reasons for higher discount rates

This lower present value would occur with higher interest rates (all other things remaining equal). In this case the expected performance of the companies would have to be expected to remain unchanged in the face of higher interest rates. Often however the competition for capital will be most intense when companies are doing well and expect to do well.

These conditions would provide good news reasons for higher interest rates and could lead to higher values, despite higher costs of capital. The bad news reason for higher interest rates is when governments are thought more likely to misbehave by adopting less encouraging economic policies for the firms that make up the economy. Bad news about government policy or about the performance of a firm inevitably translates into higher interest rates and hence less valuable companies. Good news about improving government policies and or better managed firms usually means the opposite.

We may not be able to predict share prices in the short run, but we can know when the market place is optimistic or pessimistic about the economic future.

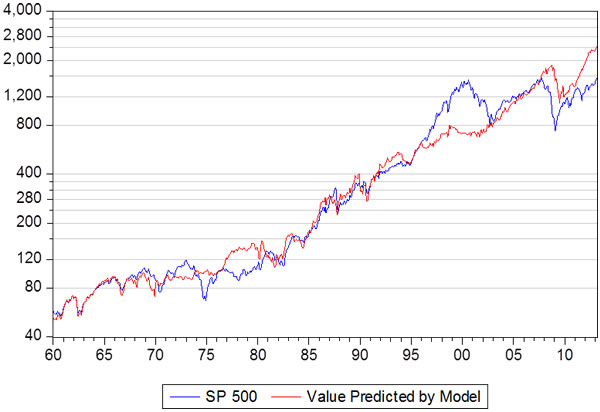

However accurately predicting the day to day moves in share prices is very difficult because expectations can change significantly as information, the news and its interpretation, percolate through the market place moving market values in a largely random way. Yet it is possible to observe when the market is more or less optimistic about the future. The best that the informed investor can hope to do is to use market values to infer how optimistic or pessimistic the market currently is about the prospects and to agree with or take issue with the prevailing sentiment. We undertake such an exercise for the value of the key share market index, the S&P 500 (representing the largest 500 companies shares listed on the New York and Nasdaq stock exchanges).

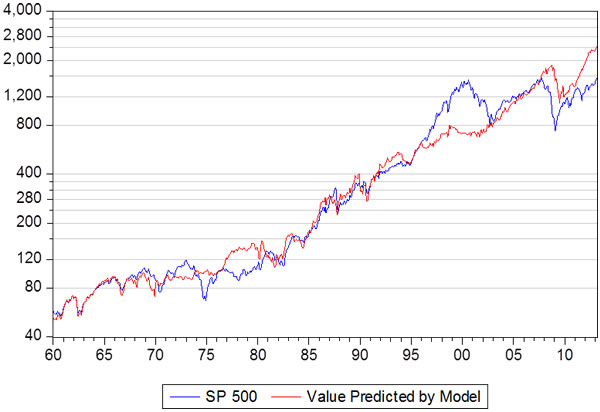

In the figure below we show the results of a simple regression equation which explains the value of the S&P 500 with reported dividends and long term US Treasury Bond Yields. This is equivalent to a present value calculation, with long term US government interest rates used as the discount rate.

As may be seen from the figure below, the explanatory power of this model is very good with actual and predicted values closely aligned in general. The goodness of fit of the model, measured by its R squared, is of the order of 95%. Thus the model may be regarded as providing a very good long term explanation of the value of the S&P 500. The S&P 500 over the long run is well explained by reported dividends and long term interest rates.

It should also be noticed that the fit was generally even closer before 2000 than since then, given the influence of the dotcom/tech bubble in the early 2000s and the Global Financial Crisis late in the decade.

The most striking conclusion to be drawn from this exercise is that the S&P 500 at the March 2013 month end, despite its recent strong gains, is still deeply undervalued by its own standards: in percentage terms about 40% below its predicted value. If the past were the guide to current performance, then the S&P 500 (given current dividends and interest rates) would have a predicted value of 2440 rather than the current (still record) level of 1560. In other words, it may be concluded that the market currently remains about as pessimistic about earnings and dividend prospects as it was at the height of the financial crisis in 2009. The same model estimated in May 2009 indicates that the market was then undervalued by 47%. As the chart shows, the S&P 500 recovered very strongly from these depressed 2009 levels over the next 24 months as prices caught up with the improved fundamentals of rising dividends and low interest rates. The same model, when estimated at the height of the stock market boom in May 2000, indicated that the market was then as much as 55% overvalued. Those times were times of extreme optimism about the prospects for listed US companies, an optimism that was not at all borne out by subsequent performance of earnings or dividends per share.

The S&P 500 Index: Actual and predicted values

Source: I-Net Bridge, Investec Wealth & Investment

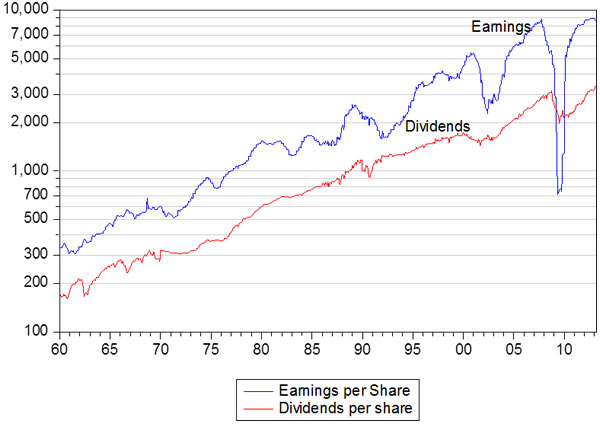

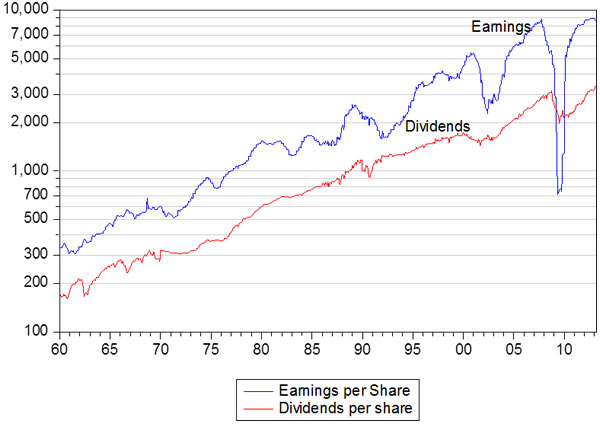

We use easily calculated dividends per share rather than earnings per share as the measure of shareholder benefits. This is because S&P 500 earnings per share collapsed so precipitously during the Global Financial Crisis of 2009 as financial corporations had to write off their many bad loans. Dividends and operating profits held up much better over this period, as we show below, and therefore provide a much better reflection of the economic performance of the companies valued between 2008 and 2013. Both series have recovered very strongly and are close to or above their pre crisis levels.

S&P 500 Earnings and dividends per share in US cents (log scale)

Source: I-Net Bridge, Investec Wealth & Investment

It may therefore be concluded that if the past is anything to go by, the S&P 500 continues to offer value. By the standards of the past the market is very undervalued for current dividends and interest rates. Pessimism, rather than optimism about economic prospects for the S&P 500, appears to dominate sentiment. The potential investor in the market can make his or her own judgments about whether such essential pessimism is still justified.

It should be appreciated that, by these measures, the market can remain undervalued for an extended period of time. It is also possible that earnings and dividends may collapse to justify such pessimism. Interest rates in the US may also rise for bad news reasons, such as less faith in the US government. They may also rise for good news reasons because US firms become more willing to undertake capital expenditure and compete, pushing up interest rates accordingly. If so, the US economy and the global economy, as well as earnings and dividends that flow from the economy, are unlikely to disappoint. Stock market valuations would then play further catch up through realised performance.

It may be of some comfort to those with a bias in favour of buying and holding shares for the long term to know that by its own standards, that is relative to past performance and current interest rates, the US equity market remains deeply undervalued despite the recent gains made.

Brian Kantor