Pretence about wages and employment harms the SA economy and the poor

There is a politically convenient illusion at the heart of SA’s dysfunctional labour market, which is well demonstrated in the balancing act forced upon the Minister of Finance in his 2013 Budget proposals.

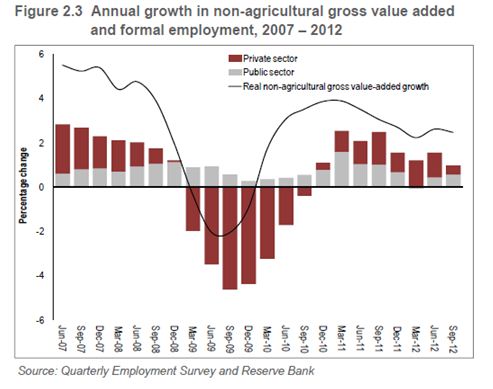

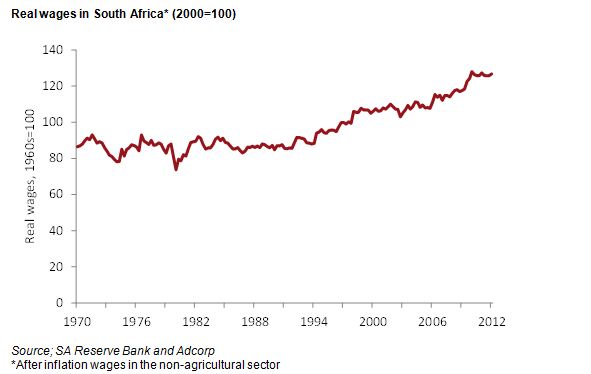

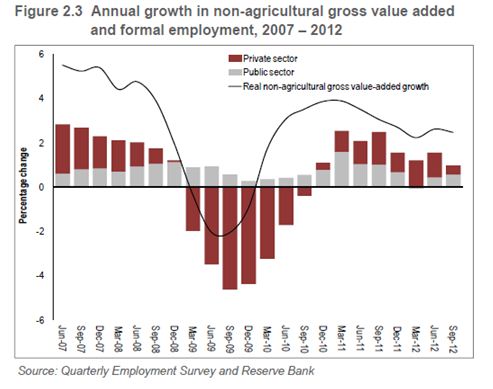

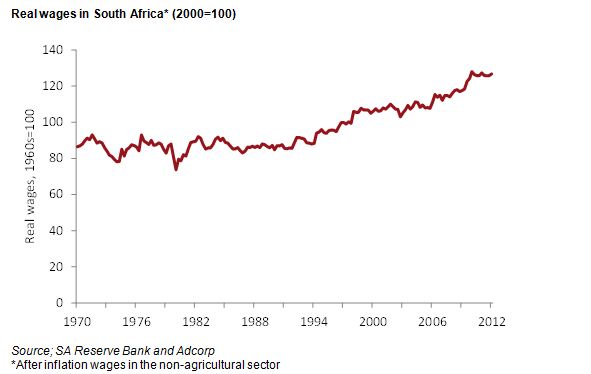

The dysfunction is the large and ever growing gap between the potential supply of labour and the demand for labour by formal sector employers. The formal economy has become ever less labour intensive, while the real wages of those in formal employment have grown significantly. The gap between real GDP and formal employment has grown consistently over the years. And competition between labour unions to represent the increasingly well paid formal sector workers has intensified, leading to unprotected strikes and the disruption of production. The figure included in the 2013 Budget Review makes the essential point: it show how the growth in GDP, or value added, has consistently exceeded the growth in the numbers employed. These are dangerous trends, crocodile jaws that might well eat up the economy unless this gap can be closed.

Employers in SA have been forced to pay higher wages by unions capable of disrupting production. Higher minimum wages and limited normal hours of work have added to the costs of hiring labour. The rights of employers and their rights of dismissal for unsatisfactory work have become highly attenuated and have added to the risks and costs of providing employment.

What is not appreciated by many in government and in the unions is that employers, sometimes to the obvious frustration of the unions and the politicians, retain the right to decide how many workers to employ. And private sector employers, with their own or their shareholders savings (capital) at risk, have responded by employing fewer workers whom they pay higher real wages but reinforce with more and superior quality machinery.

The reality for the average formal sector business is that capital has become relatively cheaper and equipment more productive while employing labour has become more expensive and maybe even less productive, when the contribution of capital to output is factored into their production functions – hence a smaller proportion of workers with formal sector jobs. And with fewer workers formally employed this means many more employed outside the formal sector, unemployed or discouraged from seeking employment.

The gains made by the formally employed have come at the expense of those who have found it so difficult to break into the ranks of the better off formally employed. Their frustrations are highly understandable but they appear to have had much less political support than the unionised workers, protected against lower wage competition. These labour market outsiders are not the only parties disadvantaged by these trends in the labour market. Artificially expensive labour is to the disadvantage of formal business as well, since they might have grown faster had they been encouraged to employ more labour. Labour intensive entrepreneurs able to compete with the established, capital intensive firms are thin on the ground.

It is not an accident that employment by government agencies has grown significantly while employment conditions have improved considerably, both in real terms and also in comparison with benefits provided in the private sector. Taxpayers have proved remarkably generous in their treatment of government employees. We cannot be definitive due to inconsistencies in the Statistics SA data, but private sector employment declined by around 1 million between 1994 and 2012 whereas government employment grew by around 1.5 million over the same period. At any rate, the public sector now employs 2.83 million people or nearly 1 in 4 formal sector workers.

This no doubt has encouraged the belief that neither wages nor the productivity of labour has anything to do with employment opportunities in the public sector, ie it is not economics but politics that determines who earns what.

The illusion is also that all employers can and should provide decent jobs with good pay. The unfortunate reality is that many South Africans and most of those without formal employment do not possess the skills to command so called decent (well paid) jobs. Therefore even when those without valuable skills manage to find work they will not easily escape poverty. Unfortunately low wage employment is the only realistic alternative to unemployment. Presumably, for many actively seeking work, low paid work would be preferred to no work at all. Given the quality of the SA labour force, and given the inadequacy of the education and training provided many South Africans during and after apartheid, the choices in the labour market are unfortunately limited to low paid work or no work.

It is this illusion that has led recently to a 50% increase in the minimum wage for agricultural workers, to a countrywide R105 per day. This is despite very different supply and demand conditions around the country. It is also despite the fact that employment in agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing (according to the Quarterly Labour Force Survey) fell precipitously from 1.362 million in September 2000 to a reported 624 000 in September 2011. The presumption must surely be that minimum wages and other regulations applied to agriculture have had a major influence on this outcome and that the higher minimum wages will lead to further losses in employment. This is so even though the higher minimum wage of R105 per day, will not enable these farm workers and their families to escape poverty.

There is a great divide between those South Africans in what may well be described as “decent jobs” and those many more who stand outside the gates and are understandably anxious to enter the more comfortable world of formal employment. The outsiders may be unemployed – actively looking for work and able to accept a job offer at short notice – or they may be working, usually for lesser benefits in the informal sector, or they may well have withdrawn from the labour market. A definitive account of the unemployed or discouraged workers as well as those working part time or full time informally is not available. We have to rely on surveys and the responses of the sample of households surveyed for evidence of employment status (which may not be reliable).

The 2011 census estimated the unemployment rate, narrowly defined as the percentage of active work seekers in the labour force as 29.8%, with the labour force being defined as the sum of the employed and unemployed. The absorption rate of the economy, that is the numbers employed as a percentage of the working age population, makes even grimmer reading: it averaged only 39.7% while the labour force participation rate (the labour force, employed and unemployed) as a percentage of the working age population was only 56.5%.

These rates varied widely by racial group and gender with black South Africans and black women the least likely to be employed or to participate in the labour force. The absorption rate for black men was estimated at 40.8% while that for black women was much lower at 28.8%. The percentage of white men of working age absorbed into employment was 75.7% while that of white women was 62.5%. The reality is that the real incomes of those in work have been rising significantly, while the numbers employed in the formal private sector have moved significantly in the other direction since the Labour Relations Act was introduced in 1995, even while the adult population and the potential supply of workers to the formal sector has grown significantly. Supply and demand for labour has not been allowed to work as it might have done with less interference.

The harsh truth is that for many South Africans unable to gain entry to formal employment, it will continue to be a choice between low pay determined by the realities of the supply and demand for labour or no pay at all. Migration from the regions of slow growth to seek work in the faster growing cities may be the only alternative to not working. Their opportunity set could however be widened significantly were the rules that govern employment opportunities to be relaxed.

It is high time, in other words, to restrain the power of the trade union movement that has been so enhanced in recent years by regulation and legislation . We can do so in several practical ways, all of which are consistent with Article 23.1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the so-called “right to work” as Loane Sharp of Adcorp has detailed (Business Day, 25 May 2012: http://www.bdlive.co.za/articles/2012/05/25/loane-sharp-sa-s-trade-unions-the-biggest-obstacle-to-job-creation#).

He suggests:

• Repealing the “closed shop” laws that compel job-seekers to join a trade union as a precondition for obtaining a job;

• Repealing the “agency shop” laws that compel workers to pay trade union membership fees whether they belong to a trade union or not;

• Requiring that trade unions ballot their members ahead of a strike, and further require that a two-thirds majority votes in favour of a strike;

• Prohibiting open ballots and requiring secret ballots, since open ballots lead to intimidation of union members who vote against a strike;

• Prohibiting employers’ collection of trade union dues on trade unions’ behalf;

• Prohibiting the automatic extension of bargaining council agreements to entire industries or sectors, so that these agreements are voluntary;

• On a nationwide basis, placing an upper limit on wage settlements, so that wage increases may not exceed labour’s marginal nominal productivity growth; and

• Making trade unions liable for the loss of company earnings that occurs during unprotected work stoppages.

The hope must be that over time increased spending on education and training will provide the entrant to the labour force with the skills that command good pay. The further hope is that the economy, helped by a much more flexible labour market, can grow fast enough to cause a shortage of unskilled labour relative to the availability of skilled labour, capital and natural resources. The competition for unskilled workers will then help in time to provide decent jobs for all. It can be much faster than trickle down – more like a torrent of real wage growth should the economy grow faster. It is certainly capable of doing this with the encouragement from a much more functional labour market. Brian Kantor