Explaining the rand – don’t look to Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), but to capital flows to explain the value of the rand

When exchange rates conform to Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), that is the exchange rate moves to compensate for differences in inflation between two trading countries, the exchange will not have any real effects on the economy. Given PPP, what is lost, say, for an exporter or gained by an importer in the form of faster or slower inflation, is fully offset by what is gained or lost by compensating movements in the exchange rate. This would leave importers or exporters no more or less competitive in their home or offshore markets. PPP exchange rates are however at best a very long run equilibrium rate to which exchange rates may trend but seldom conform.

The SA experience with exchange rates is one where large deviations from PPP exchange rates are the rule rather than the exception. The starting point for any calculation of PPP equivalent exchange rates is of crucial importance. The date should be be one when the exchange rate appears very close to its long term PPP value.

This was the case for the rand/US dollar in 1995. Before 1995 the value of the commercial rand (this was used to pay for imports, dividends and interest and dividend payments abroad and received for exports) was protected by exchange controls on both foreign and domestic investors. Flows of capital to and from SA were conducted through the transfer of a more or less fixed pool of so called financial rands. These financial rand movements, usually expressed as a discount to the commercial rand, left the value of the commercial rand largely unaffected by capital flows and insulated against changes in investor sentiment. Hence foreign trade driven commercial rand exchange rates stayed very close to their PPP values, as was the case in 1995.

The capital controls applied to foreign investors in the form of the financial rand were abandoned in 1995. Ever since then, flows of foreign capital to or from SA – driven by levels of SA or global risk tolerance – came to influence the value of the unified rand. The rand became less a trading and more a capital driven currency in the short run.

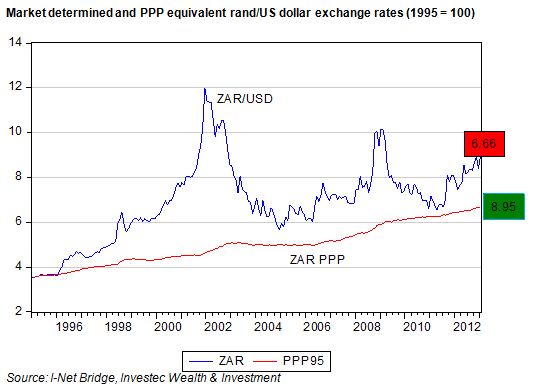

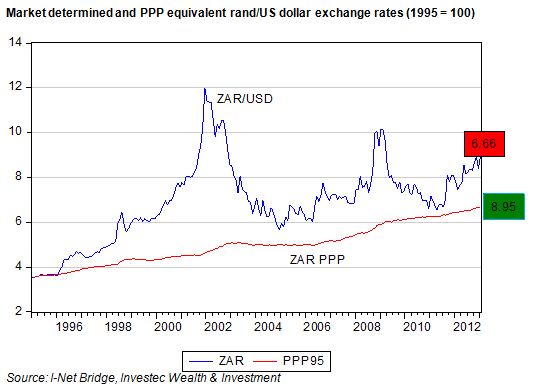

We show below (starting our calculation of the PPP equivalent rand/US dollar exchange in 1995) that the rand had become deeply undervalued by 2000. If PPP had held between 1995 and 2013, the US dollar that cost R3.35 in January 1995 would have cost a mere R6.66 in January 2013, leaving the rand about 28% undervalued compared to its PPP value.

If we start the same calculation in January 2000, when the US dollar fetched R6.31 and had PPP equivalent exchange rates been maintained, the US dollar would now cost R9.68, making the rand appear 10.5% overvalued. However, as we have shown, the PPP equivalent value of the rand in January 2000, using January 1995 as the starting point, was as little as R4.36, not the R6.31 it cost. The rand, as a result of freed up capital movements after 1995, was already deeply undervalued by 2000. It was to become much more deeply undervalued in 2001, but thereafter began to recover with improved investor sentiment.

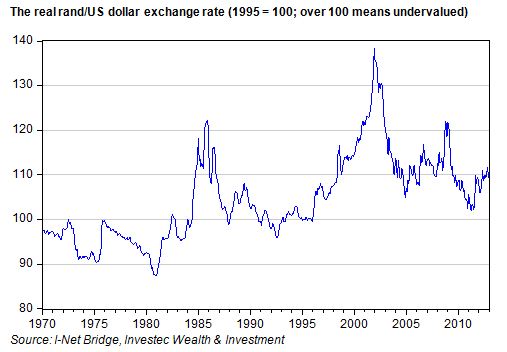

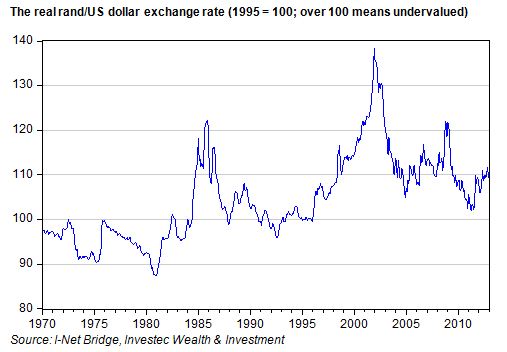

In the figure below we show the real rand/US dollar exchange rate, that is the deviation in the value of the rand from PPP, taking 1995 as the starting point. The real commercial (then unified) rand has fluctuated wildly over the years. It was slightly overvalued during the gold boom seventies. It weakened significantly when SA failed to cross its political Rubicon in 1986. The largest burst of weakness came in 2001 for SA specific reasons – largely related to the panic demands for asset swaps when they first became available – and the real rand lost as much as 40% of its value. Thereafter it began a more or less consistent recovery, helped by large foreign flows into the JSE (though it was interrupted by the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 that weakened all riskier emerging market currencies). The strength of the rand and the JSE after 2003 was not at all coincidental. The recent weakness of the rand, very much SA specific, has moved the real rand from near parity with the US dollar to about 10% undervalued.

Clearly it is investor sentiment that has come to drive movements in the exchange value of the rand. Sometimes these perceptions are SA specific and at other times much more generally explained by global attitudes to risk taking.

The reality for SA exporters and importers post 1995 is that they have had to cope with a highly variable real exchange rate. It is instructive to note that the extreme moves between 1983 and 1986 can also be explained by capital flows: the financial rand was temporarily abolished in 1983 and then reinstated in 1986.

It is these exchange rate fluctuations that greatly complicate the business of importing and exporting. Ideally, given consistency of economic policies, the real exchange rate would stabilise. Unfortunately fiscal and monetary policy in SA has been far more consistent than expectations of them. It is these expectations of policy that drive capital flows more than the policies themselves. Until SA can convince investors of the permanence of investor friendly policies, such real exchange rate volatility will continue.

The advice for SA policy makers is to maintain investor friendly policies, including the freedom to move capital in and out of the SA economy. The depth of the SA capital markets and the consequent liquidity it offers has been a major attraction for foreign investors, upon which the SA economy remains highly dependent for its growth, given the lack of domestic savings. The economy will have to trade off exchange rate instability against easy access to foreign capital.

Resorting to capital controls would drive capital away over any long term view. Moreover improved labour relations would be highly investor friendly. It would lead to a stronger real rand and a sronger economy supported by larger capital inflows. Brian Kantor