Christine Lagarde, now head of the IMF and recently Minister of Finance in the Sakorzy government, told the Jackson Hole Conference of central bankers on Saturday of the three key steps that Europe should take to work its way out of crisis:

Step 1 she recommended, was to “… sustain sovereign finances – more fiscal action and more financing….” and cautioned that this did not require “…. drastic upfront belt-tightening—if countries address long-term fiscal risks like rising pension costs or healthcare spending, they will have more space in the short run to support growth and jobs. But without a credible financing path, fiscal adjustment will be doomed to fail. After all, deciding on a deficit path is one thing, getting the money to finance it is another. Sufficient financing can come from the private or official sector—including continued support from the ECB, with full backup of the euro area members.”

Step 2 was more urgent and perhaps more controversial.

That is to say, European banks “….need urgent recapitalization. They must be strong enough to withstand the risks of sovereigns and weak growth. This is key to cutting the chains of contagion. ……The most efficient solution would be mandatory substantial recapitalization—seeking private resources first, but using public funds if necessary. One option would be to mobilize EFSF or other European-wide funding to recapitalize banks directly, which would avoid placing even greater burdens on vulnerable sovereigns…..”

European banks face a large difficulty that is not of their own making. Holding debt issued by their own sovereigns has always been regarded as the safest way for banks to lend out the cash they take in as deposits. Indeed they are often required by regulators to hold significant quantities of securities issued by the government and its agencies. Holding the debt issued by foreign governments has been optional for banks and some governments are more risky than others and pay higher interest rates accordingly. European banks currently own 45% of all European Government debt: some good, some bad and some downright ugly.

The notion that members of the Euro monetary union could default on their debts was unthinkable until recently. Ordinarily governments escape default on debt denominated in their own currency by requiring their central banks to monetize their debt.

The problem when a government is printing cash to fund its expenditure is potential inflation, not default. But, in the terms of the European Monetary Union, only the European Central Bank (ECB) can issue more euros. In the absence of a fiscal union to accompany a monetary union, such powers to print money to resolve a banking crisis have been compromised by national rather European interests. The fiscally sound members of the monetary union, mostly located in Northern Europe, are reluctant to subsidise the fiscally irresponsible members of the union to the south of them. For the central bank to treat all the government bonds issued by all European governments as having the same face value when exchanged for ECB deposits would mean a subsidy to the profligate.

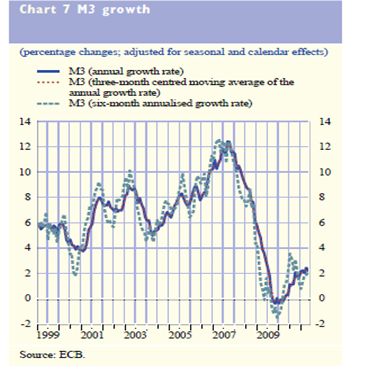

In reality the ECB has been accepting government securities of all kinds without distinction offered to it by all European banks in exchange for cash at its discount or repurchase window. It has pumped in large supplies of cash to European banks who have demanded cash from the ECB, accompanied by collateral in the form of Euro government debt. Such action is within its discretionary powers. Had it not lent so freely Europe would have suffered a run on all its banks and a liquidity crisis. The decline in the yields on Italian and Spanish government bonds has revealed the success these ECB purchases have had in calming the Euro bond market.

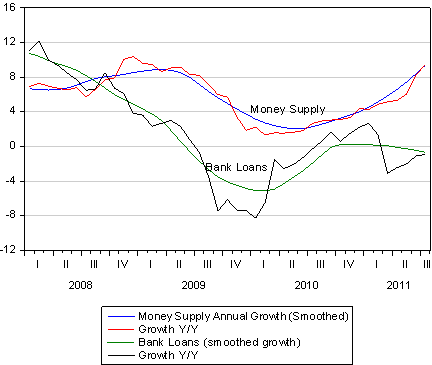

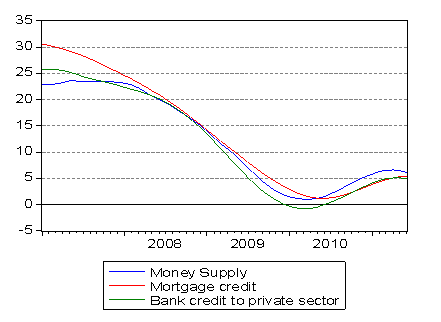

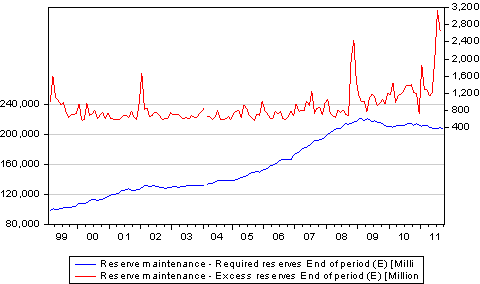

That there is no liquidity crisis in Europe is identified by the increase in the cash held by European banks well in excess of their legal requirements to hold cash. As we show below European banks are following the example of the US counterparts in building up their cash reserves at the expense of their lending.

What the ECB cannot do of its own volition is the equivalent of the QE2 or TARP (Troubled Assets Recovery Program) activities conducted by the US Fed and the US Treasury. That is, they cannot go directly into the markets and offer to buy government securities and mortgage backed securities on a large scale to inject liquidity and (more important in the case of TARP) to inject fresh capital into the banks and other financial institutions.

As Mme Legarde has identified, it is capital rather than cash that the European banks are short of. Such a need to raise more capital is reflected by the lower values attached to the shares of European banks. European banks are trading at about half the value of the assets on their books. Their books have an important part made up of suspect government securities which may not have been written down to reflect market realities; while the scope for increasing the size of their books is impaired by the weak Euro economies. This decline in the equity market value of the banks makes them more vulnerable and less able to raise meaningful amounts of capital from their shareholders.

They need the equivalent of a Warren Buffett to come to their rescue, as he did with Bank of America. Failing this shareholders may have no choice but to subscribe to deeply discounted rights issues offered by banks that might otherwise go out of business. The further alternative is of course to rely on governments to subscribe to the capital of banks. The banks may hope that capital provided by governments is a temporary provision (as it has proved to be in the US where banks have paid back the government with a profit) and also not accompanied by too much political interference in the business of banking.

This then brings the discussion to step 3, which Lagarde believes Europe will have to take if it is to enjoy a full recovery and retain its monetary and banking systems in more or less their present form.

To quote her: “Europe needs a common vision for its future. The current economic turmoil has exposed some serious flaws in the architecture of the eurozone, flaws that threaten the sustainability of the entire project. In such an atmosphere, there is no room for ambivalence about its future direction. An unclear or confused message will add to market uncertainty and magnify the eurozone’s economic tensions. So Europe must recommit credibly to a common vision, and it needs to be built on solid foundations—including, for example, fiscal rules that actually work.”

The European monetary union is being sustained by the ability of the ECB to print money to keep its banks and governments afloat. The crisis is being overcome this way. Any permanent solution to the issues Europe faces requires fiscal stability and a fiscal union that effectively limits government spending in Europe to what European taxpayers can support. The hope for Europe is that fiscal responsibility can only be realized by governments spending less – especially in ways that discourage the work, savings and enterprise of its citizens. The limits to the taxes European governments can collect has long been exceeded, as its fiscal crisis makes clear.