The Reserve Bank has indicated very clearly that it does not intend to provide any further relief for the hard pressed SA economy. Neither lower interest rates, nor quantitative easing, is on offer for the foreseeable future.

The Reserve Bank is relying on waiting to quote its release:

“….There are however signs that the downturn, both globally and domestically, may be nearing the lower turning point, but the recovery is expected to be slow and protracted…”

It added later that:

“….The composite leading indicator as compiled by the staff of the South African Reserve Bank increased slightly in April. The indicator suggests that the lower turning point in the cycle could be reached later in the year.”

We would agree that while the global economy may well have reached its lower turning point, we are not at all sure that the SA economy has done so. We do not share confidence in the predictive powers of a leading indicator much influenced by the stock market. The housing market is probably more important than the stock market in influencing the wealth and confidence of the SA consumer and trends there are not at all helpful.

The economy is very dependent on global trends

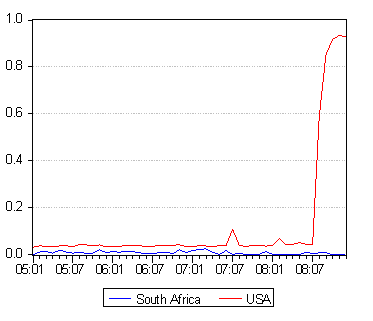

The reluctance to lower interest rates further or to engage in quantitative easing

(linked to attempts to restrain rand strength) has made the recovery of the SA economy dependent on global trends. The outlook for domestic spending remains bleak as the Reserve Bank has confirmed.

Unintended consequences

In response to the decision the rand responded favourably to the prospect of higher short term rates while higher long term rates followed short rates higher.

The compensation for inflation offered in the bond market, being the difference between the yields on the inflation linked government bonds and the vanilla variety (to which the Bank gives attention in its focus on inflationary expectations) rose yesterday. The yields on the inflation linkers declined reflecting the poorer growth outlook while the nominal yields rose.

A stronger rand and higher interest rates are surely not desirable outcomes of monetary policy settings. The stock market and also the exchange value of the rand however are responding to forces beyond the influence of SA monetary policy. The stock market is largely ignoring the deteriorating outlook for the earnings of SA economy dependent companies.

Global forces dominate the rand and the JSE

The dominant forces acting on the JSE and the rand are the direction of Emerging Equity Markets and commodity prices – they are running together in response to the outlook for the global economy. This outlook has improved significantly over the past few days in response to OECD economic forecasts that were revised higher rather lower.

The Reserve Bank is fighting inflationary expectations

The focus of the MPC statement was on inflation and inflationary expectations. The Reserve Bank argument against lowering interest rates is a familiar one. That is to contain inflationary expectations – even while recognising that the weak state of the economy – may well lead inflation lower. They also make reference to producer prices that are falling sharply and that unlike consumer prices, do decisively reveal the weak state of domestic demand as well as the influence of the strong rand on the competition for domestic producers. That producer prices might better reflect the thrust of monetary policy and that if they do, deflation may be a greater threat to the economy, does not receive consideration.

Are inflationary expectations self fulfilling?

The Reserve Bank is of the view that inflationary expectations are self fulfilling, even if the economy is suffering form excess supply rather than excess demand. The long run benefits of less inflation expected and therefore less inflation – as it is assumed – is thought to be the worth the short term sacrifices the economy has to make.

How the Reserve Bank could hold to this view now given producer prices, is very hard to appreciate. Our view is that inflationary expectations, when applying some naïve cost plus view of price determination, can only lead to permanently higher inflation when supported by a willingness of consumers to spend more.

The current unwillingness of SA consumers to pay more is obvious. The Bank also is well aware that the pressures on consumer prices are coming from prices that are regulated rather than market determined – and therefore well beyond the direct influence of monetary policy. Such price increases however act as a tax on expenditure and depress demands for less dispensable goods and service. Tax increases provide reason for lower rather than higher interest rates.

An alternative explanation for more inflation expected

The Reserve Bank might however consider another reason for the unhelpful trends in inflation expected, other than inflation trends themselves. That is a single minded focus on fighting inflation- in rhetoric perhaps more than in practice – is politically unsustainable. If so this is expected to damage the independence of the Reserve Bank to continue its fight against inflation over the long run. Apres moi le deluge is not an unrealistic conclusion, one leading to more inflation expected over the long run.

We share the view that low rates of inflation are helpful for economic growth in the long run. But to regard inflation as the end rather than the means of economic policy regardless of the state of the economy, is neither necessary or helpful to the cause. The decision of the Reserve Bank not to lower interest rates now will add doubts as to the usefulness of low rates of inflation when the sacrifices for it seem so heavy and do not make obvious sense. The political consequences of Reserve Bank inaction are not necessarily encouraging for the inflation outlook.

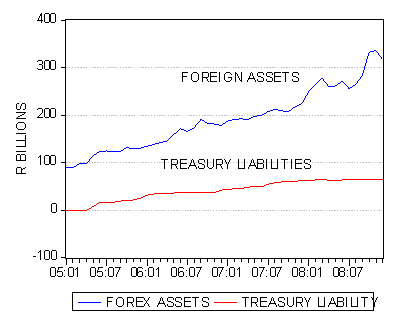

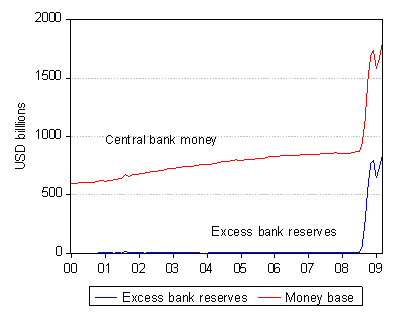

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Securities

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Securities