Well maintained homes in my neighbourhood continue to be demolished at an impressive rate. Demolition in is being ordered so that the land released can be converted to a new residential unit or two or more. A process also well under way widely in the Western Cape. But conspicuous by its absence in much of the rest of SA.

If the demolition is to make economic sense the to be realised market value of the new units constructed must be expected to exceed the purchase price of the old building, the significant costs of constructing the new units, the demolition costs and the interest income sacrificed on the working capital tied up in the project would have to be covered as would the price paid for the established building demolished or expensively redeveloped. The purchase price paid will be approximately equal to the present value of the future rentals being sacrificed on demolition.

Any extant building survives because a potential re-development of it does not meet this profit test. Most buildings (slowly) survive the test of time. Look around you. It takes rising rentals, or rental income effectively sacrificed by owner occupiers, to encourage re-development. Escalating rentals add value to homes or commercial buildings and encourage owners to sell up and move on. And add value, that is additional wealth and spending power for their owners. It takes a growing economy to change the face of the nation.

Sadly, for the average home or building owner in South Africa, or those owning commercial property, the rental tide has been receding, outside of the Cape. The legitimate dreams, based on past performance, of millions of homeowners and landlords of buildings generating hoped for wealth for them, has been frustrated. They should blame the national government for the economic policies that have failed. And moreover, blame local governments who, egregiously, have raised taxes on their homes to deliver far inferior services in exchange. Terrible wealth destroyers they have proved to be.

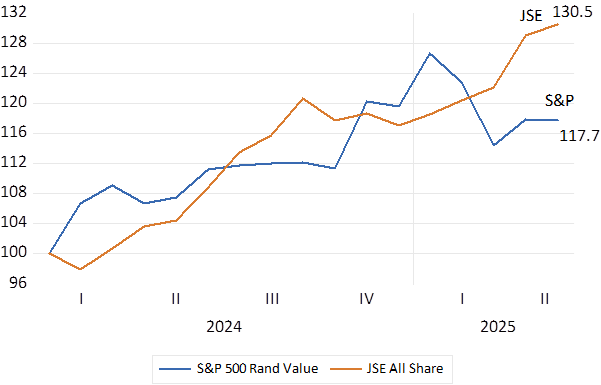

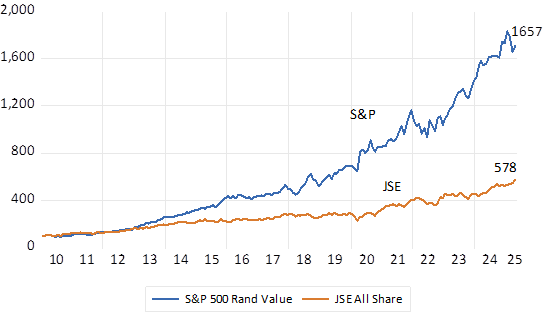

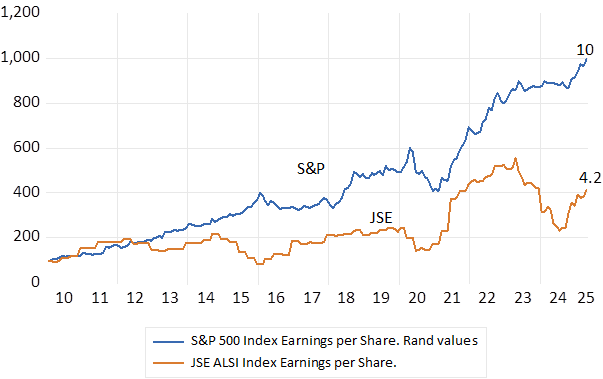

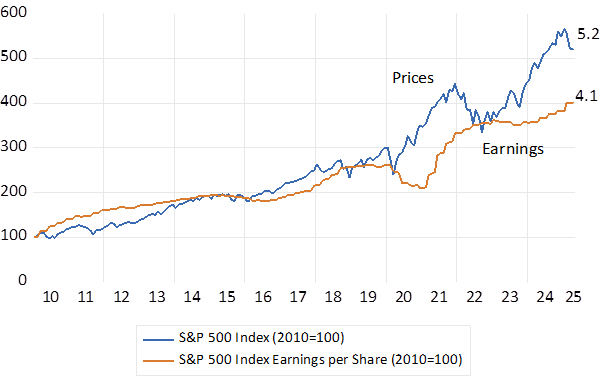

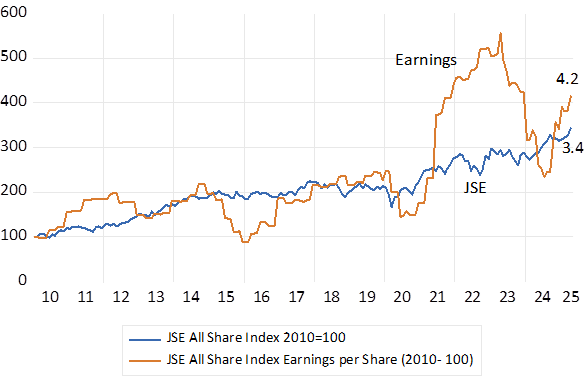

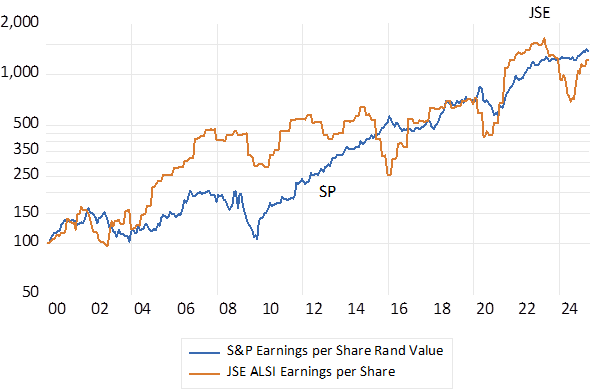

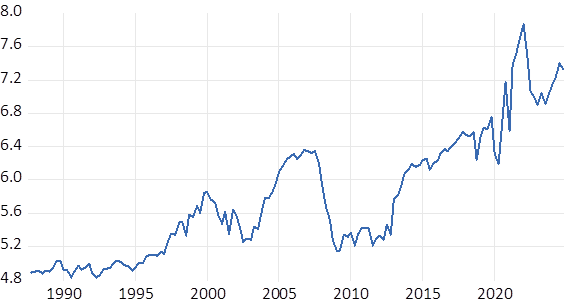

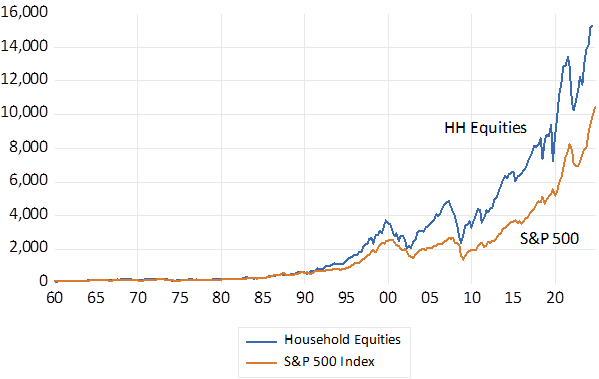

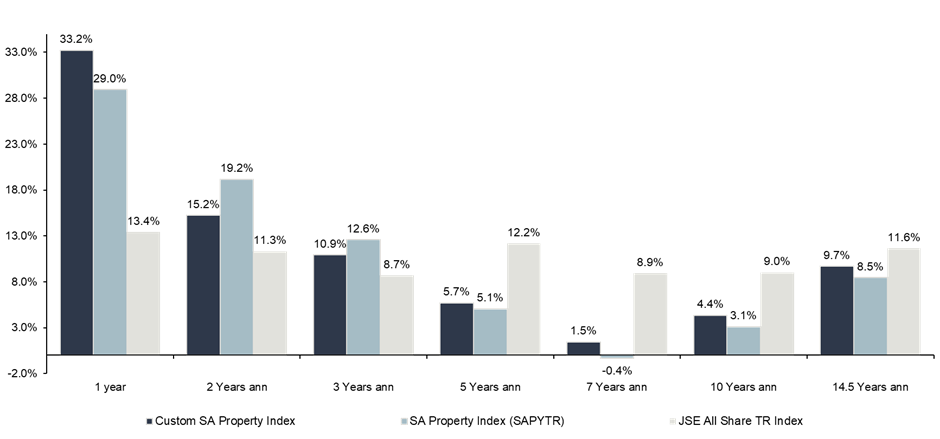

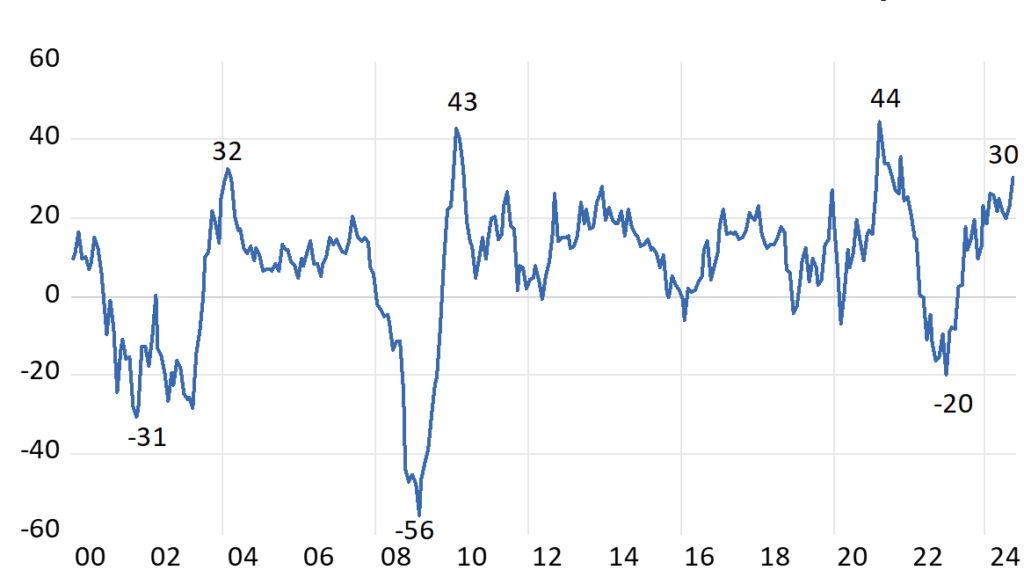

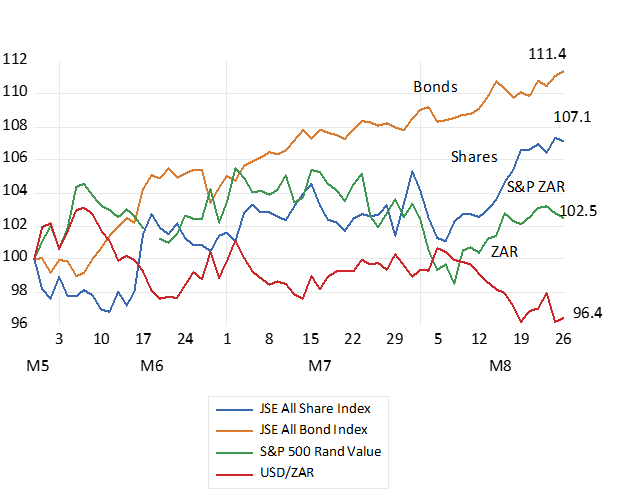

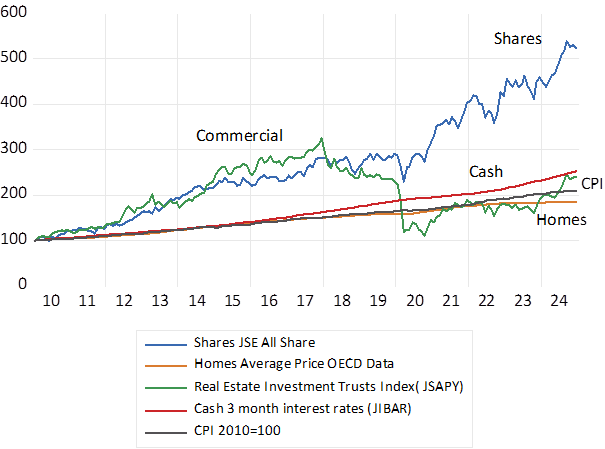

Between 2010 and 2024, annual returns calculated from owning the average home, including rental income, assumed to have increased at the rate of inflation, and reinvested or used to pay down mortgage debt, was on average 4.2% p.a. Annual average returns from the listed REITS have been an average 5.6% p.a. while the JSE delivered much more, 11.7% p.a. on average, also including dividends reinvested. Even the low-risk money market returned more than homes or listed real estate. Some 6.2% p.a. on average. Inflation averaged 5.1% over the fifteen years. A million rand invested fifteen years ago in the stock market would be worth R5.3m today, the average million rand home then would fetch but R1.84m and an average R1m portfolio of commercial and industrial property would by now have compounded to about R2.5m. That is by about the same increases in the prices of the average basket of consumer goods, up by about 200% in the fifteen years.

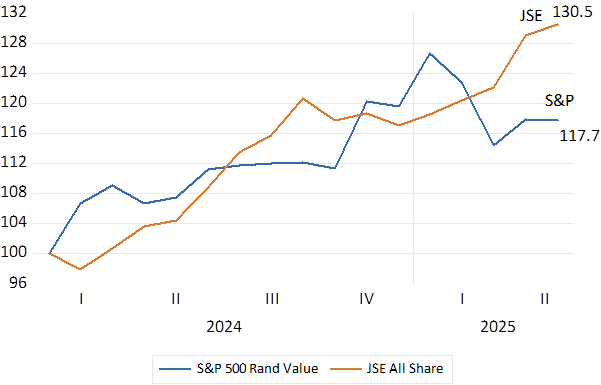

Investment Returns; Shares, Real Estate. Cash (Income reinvested) and the CPI. 2010-2024 (2010=100)

Source; OECD, Reserve Bank of South Africa and Investec Wealth and Investment

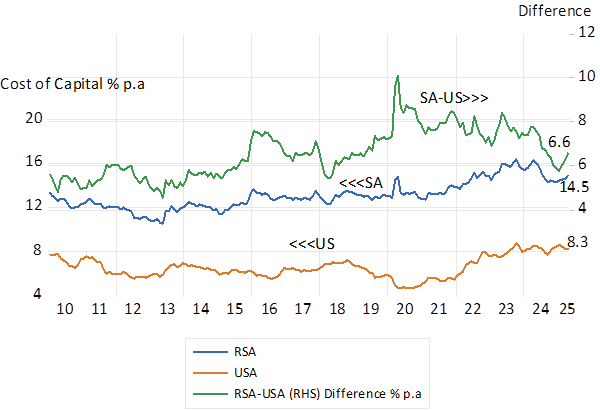

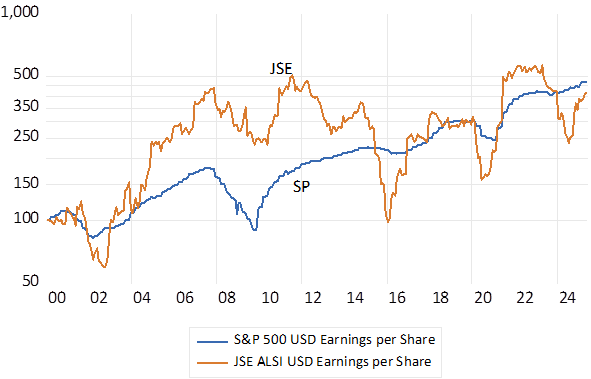

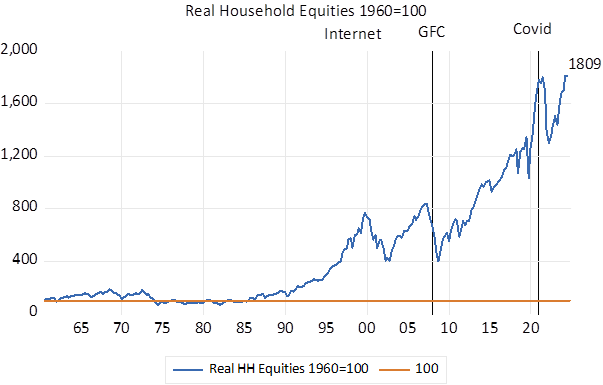

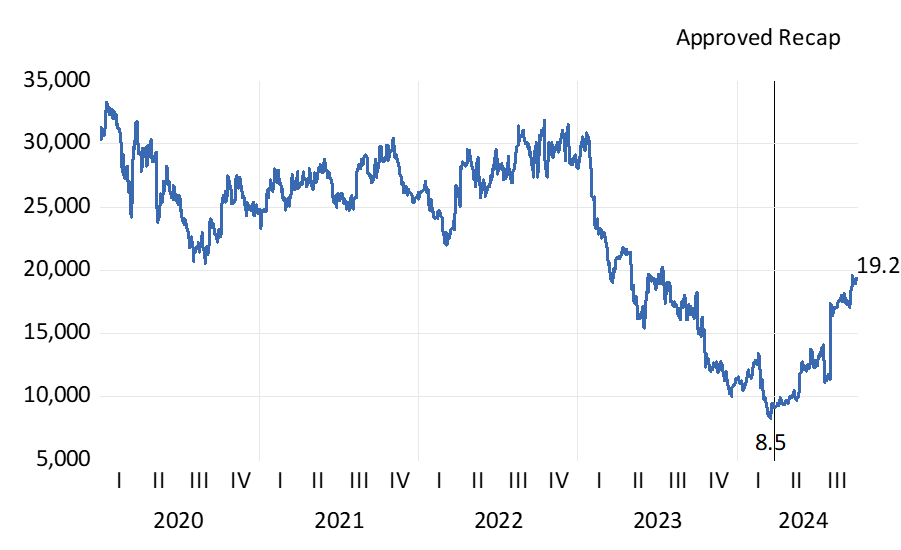

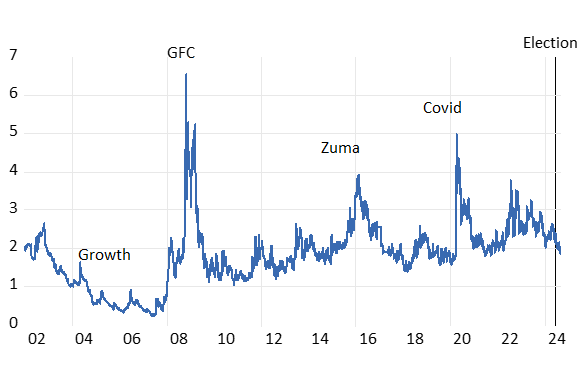

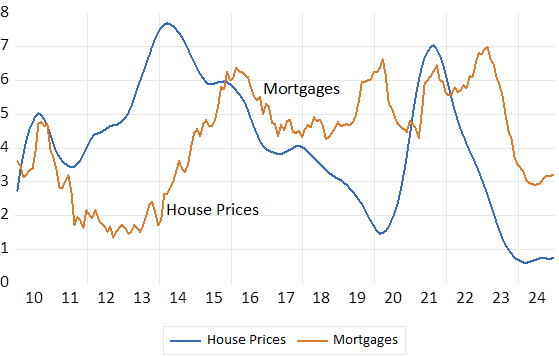

Consistently, the average increase in mortgage advances since 2010 has averaged but 4.3% p.a. close to the average increase in house prices. Recently this growth rate has fallen further to about 2% p.a. The housing market has not been particularly good for banks- or might one say the banks, especially the Reserve Bank, has not been very good for the housing market, given very expensive mortgage loans.

Annual growth in house prices and mortgage advances (2010-2024)

Source; OECD, Reserve Bank of South Africa and Investec Wealth and Investment

If, a big IF, you could have rented your dream home fifteen years ago you would have done better renting than owning. Especially if you had saved the difference between the cash rent paid and the mortgage interest rate – say a 5% p.a average yield gap – into the share market.

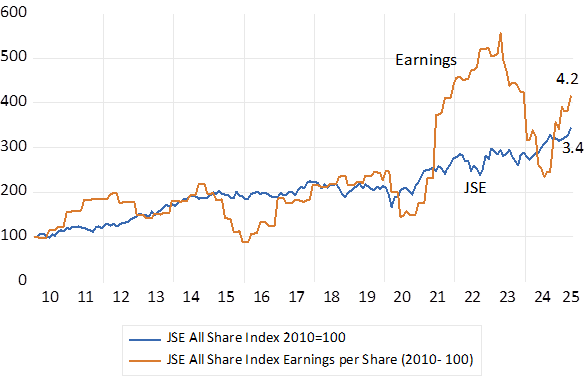

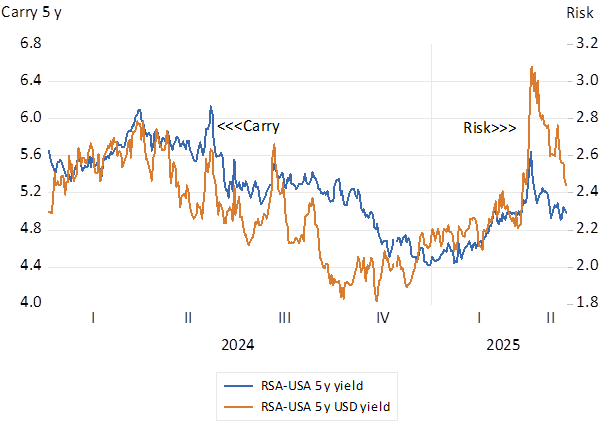

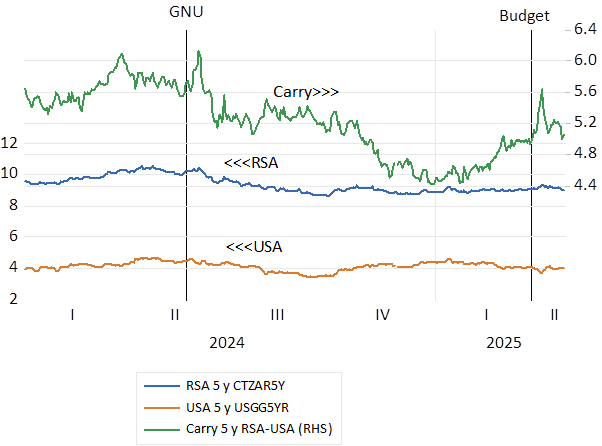

The total internal investment return on a property is the sum of the initial year one rental yield plus the rate at which the rents are expected to escalate over say the next 15 years. For much of the past 15 years the expectations of rental escalations and consequent capital gains must have been disappointed (outside the Cape) Thus renters rather than owners would have been favoured by the persistent gap between lower rental yields and higher mortgage rates.

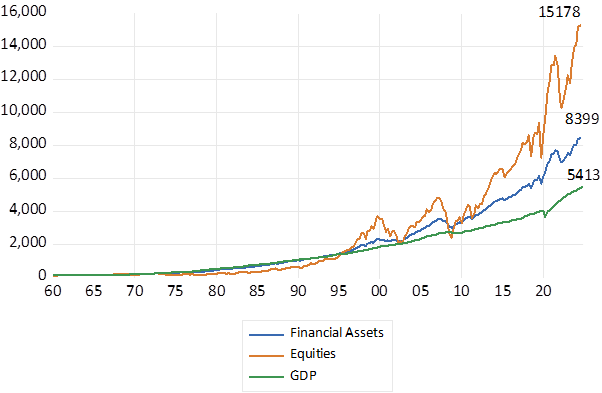

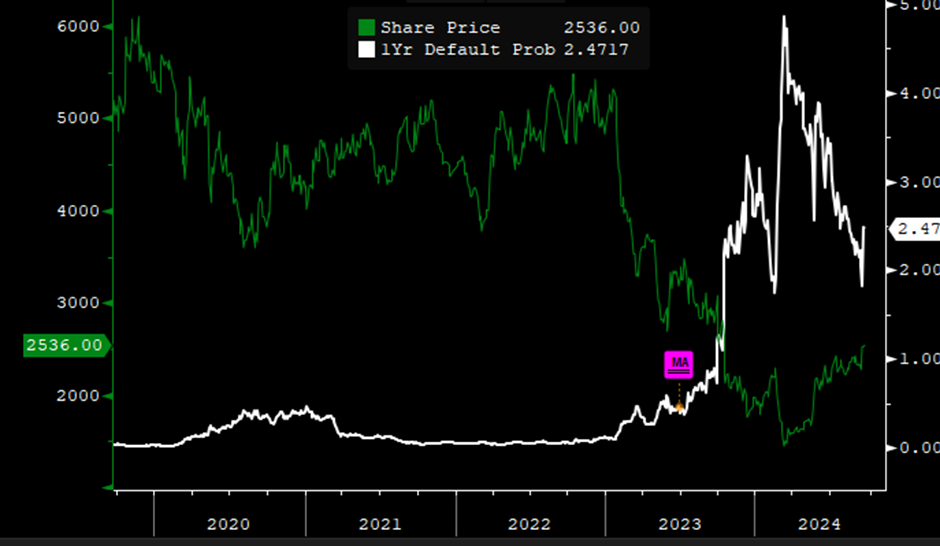

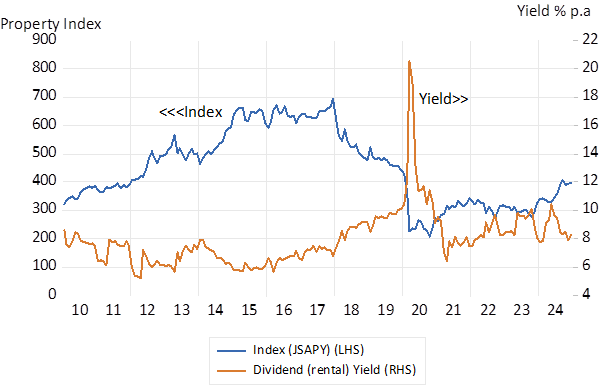

What comes next for renters or owners of real estate will depend on the state of the economy and the competence of municipal authorities. If property prices and rentals continue to rise at their recent pedestrian price, rental yields will rise to compete with punishingly high borrowing costs. Initial rental yields, (Rents/Value) will rise as the expected capital gains owning property fall away. Though rentals themselves may not rise much, given a depressed lack of demand for the space available. As has clearly happened with commercial property and the REITS. Much of the return from their shares is coming in the form of dividends paid.

Real Estate Investment Trusts on the JSE. Index values and Dividend (net rental) Yields (2010-2024)

Source; OECD, Reserve Bank of South Africa and Investec Wealth and Investment

A revival of the economy and the property market with it could change the trajectory of real estate values, and help create income and wealth for many homeowners. And revive the construction sector in the old-fashioned way. By turning the old into the new to revitalise our cities and suburbs. It can happen with a clear vote for better governance, better policies and their execution. Surely very much possible – as the Cape proves.