An extraordinary week has passed. When the government ordered and prepared for a shut-down of much (how much??) economic activity to deal with the health crisis. All, including the participants in capital markets, have tried to come to terms with the evolving realities at home and abroad. And it was a week when the SA Reserve Bank moved from conventional to unconventional monetary policy.

The Bank at its monetary policy proceedings on the 17th March reported in an explicitly conventional way. It cut its key repo rate by an unusually large 100bp- on an improved inflation outlook. By the 25th March it was practicing Quantitative Easing (QE) buying RSA bonds in the market to reduce “…excessive volatility in the prices of government bonds…” and freely providing loans to the banks of up to 12 months.

The Bank is therefore creating money of its own volition. Cash reserves, that is deposits of the private banks with the Reserve Bank, are created automatically when the Reserve Bank buys government bonds and shorter-term from the banks or its customers. These deposits serve as money – and are created without any cost to the issuer- the central bank- acting as the agent of the government. These additional cash reserves support the balance sheets of the banks. And could lead to extra lending by them, as is the intention

Had the Reserve Bank not acted as it did, the bond market would surely have remained volatile. But more importantly it might not have been able to absorb a deluge of bonds and bills that the government would be issuing to fund its emergency spending. Including coping with a draw-down of R30b of bonds sold by the Unemployment Insurance Fund to generate cash for the government to spend on income relief.

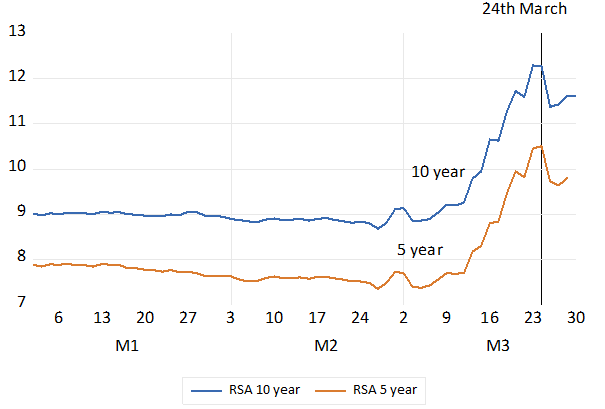

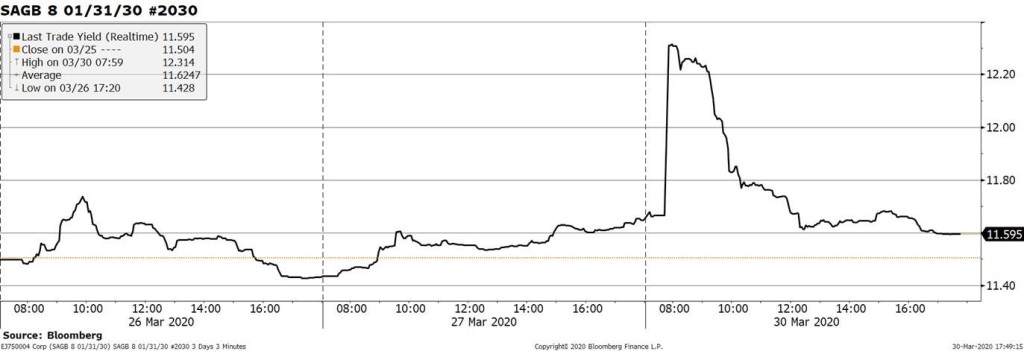

The yield on the 10 year RSA was about 9% p.a. in early March. By March 24th it was over 12% p.a. and declined marginally in response to the Reserve Bank intervention. The derating of SA credit by Moody’s on the Friday evening, after the market had closed, seemed inevitable in the circumstances. On the Monday morning the yields on long dated RSA bonds jumped higher on the opening of the market and then receded and ended as they were at the close on Friday (see figures below)

RSA Five and Ten-Year Bond Yields Daily Data 2020 to March 27th

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

RSA 10 year Bond yield 26 -30 March Intra day movements

Central banks all over the world are also doing money creation – in very great quantities. Doing so as a predictable response to their own lock downs and collapse of economic activity and its threats to financial stability. But in the developed world they deal for bonds and other securities at much lower interest rates. Though no doubt the scale of their bond and other asset buying programmes (QE) is part of the explanation for very low yields – both short and long. Yet despite money creation on a vast scale more inflation is not expected in the developed world.

Not so in SA as we have indicated and in many other emerging markets. Issuing longer dated government bonds in their own currencies is a very expensive exercise. And has become more expensive post Corona.

Lenders to emerging market governments, in their own currencies, demand compensation for high rates of inflation expected, and receive compensation for the inflation risks There is always the chance that the purchasing power of interest income contracted for, and the real value of the debt when repaid, will be eroded by inflation of the local currency.

The danger is that fiscally strained governments will, sometime in the future, yield to the temptation to inflate their way out of the constraints imposed by bond investors. By turning to their central banks, to fund their spending to a lesser or greater degree, rather than to an ever more demanding bond market. Issuing money (creating deposits) at the central bank to finance spending carries no interest cost. It can be highly inflationary depending on how much money is created and how quickly the banks use the extra cash to extend loans to their customers.

The growing risk that SA would get itself into a debt trap and create money to get out of it has been the major force driving long-term RSA yields on RSA debt higher in recent years. Higher both absolutely and relative to interest rates in the developed world. Bond yields have risen for fear that SA would create money for the government to spend in response to ever growing budget deficits and borrowing requirements and a fast-growing interest bill. As the SA government has now done with the co-operation of the Reserve Bank- though in truly exceptional circumstances and justifiably so.

Avoiding the debt trap, controlling budget deficits and convincing investors and credit rating agencies that the country can fund its spending over the long term without resort to money creation, is the task of fiscal policy. For SA to regain a reputation for fiscal conservatism and an investment grade credit rating is now more unlikely than it was when a promising realistic Budget was presented in February.

The Reserve Bank may hope to control domestic spending and so inflation through its interest rate settings. It does not however control inflation expected and so the interest rates established in the bond market. The more inflation expected the higher will be interest rates. Expected inflation over the long run is dependent in part on the expected fiscal trends and the likelihood of a resort to money creation. And these fiscal trends, thanks to Corona virus, have deteriorated as they have almost everywhere else.

How therefore should the government and the Reserve Bank react to current conditions in the bond market? Long term yields are unlikely to recede significantly; and the yield curve is likely to get steeper should the Reserve Bank reduce its repo rate further – as it is likely to do.

The government should therefore fund as much as it can at the cheapest, very short end of the capital market. To issue more short dated Treasury Bills to fund current spending and to replace long dated Bonds as they mature with shorter term obligations. It will save much interest this way. The actions of the Reserve Bank by adding liquidity (cash) to the money market through QE will have made it much easier to borrow short from the banks and others.

And when the economic crisis is behind us it will remain essential to strictly control government spending to regain access to the long end of the bond market on more favourable terms. Only the consistent practice of fiscal discipline will deserve and receive lower longer-term borrowing costs.